Hello Embedded World

While doing research for possible master thesis topics, I’m looking into the idea of wireless sensor network. At KULeuven the DISTRINET research group is spending quiet some effort into this and I want to make sure that I fully understand it before I decide to move in this direction or not.

For me this means going back to the basics and work my way up from the bottom. This page is about bootstrapping my way into the embedded world. It follows up on my first steps in electronics and aims to get a Hello World style implementation running on a member of the AVR processor family.

The sections below are mostly pointers to separate pages, discussing each of the components and their use. Consider them a table of contents to a track from nothing to a working setup, ready to build further upon.

Sources

Maybe the most important lesson in technology is that most of the time things have been done before by someone else. Although I’m writing these pages I think it is very important to mention that I cannot take credit for the fundamental content - maybe for bringing it together in a clean format, but that’s a different value ;-)

To allow you to refer to the sources I’ve consulted, I try to keep track of them in the list below:

- https://www.sparkfun.com/tutorials/57 ↗

- https://www.sparkfun.com/tutorials/93 ↗

- https://www.sparkfun.com/tutorials/95 ↗

- https://www.sparkfun.com/tutorials/104 ↗

- http://www.codehosting.net/blog/BlogEngine/post/Programming-the-ATmega168.aspx ↗

- http://adentranter.blogspot.be/2011/03/atmega168-hello-world.html ↗

- http://wiki.blinkenarea.org/index.php/DotBloxEnglish ↗

And of course … Google ↗ is, also for embedded systems, your best friend ;-)

Step 1 : Power

The wall socket in your house gives you 110 to 240V, depending on your physical location in the world. Embedded systems typically use much lower voltages. Also the current you get from the wall socket is typically AC (Alternating Current). Embedded systems typically use DC (Direct Current). They are also much more susceptible to glitches in their power supply.

Therefore it is important to have a very stable power supply to hook up your designs. There are basically two ways to get your systems powered: batteries and via an adapter, connected to the electric grid.

So the first thing todo, is to create a regulated voltage power supply.

Step 2 : Putting Code onto the Processor

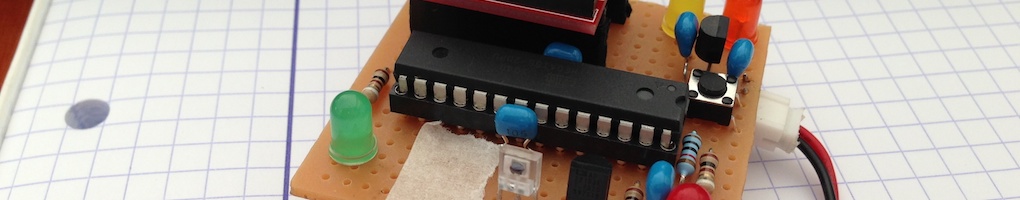

At this point in time (April 2013) I had an Atmel ATMEGA168 lying around, so that’s what I started out with. It’s part of the AVR family, a range of very popular processors these days.

Time to hook up the ATMega168.

Step 3 : Adding a Serial Interface

What do real programmers use to debug software ? Right, printf. And that’s what I also want to do from my ATMEGA168. So let’s add a good old serial interface to the board that allows us to use printf and have it displayed on our terminal window on our full fletched computer.

Next steps - aka coming soon

Below is a list of components I want to add/experiment with to cover a reasonable classic scope of what you want/need when designing embedded systems.

Basically my TODO list …

- flash memory

- sensors: temperature, light, accelerometer, …

- usb serial communication

- wireless communication: RF, WiFi, Zigbee

vCard

vCard

Homemade by CVG

Homemade by CVG My Homemade Apps

My Homemade Apps Thingiverse

Thingiverse

Strava

Strava