The Solution Split

Starting 2025 marked the end of my first 25 years in the IT industry and the beginning of another chapter that will span approximately the next 15 years. It also coincided with my 50th birthday, halfway through 2024, prompting me to reflect even more on this significant turning point. It was during a weekend trip to Disneyland Paris with my children, that I gained clarity on what I needed to do. Conceptually at that point, since it required substantial changes, and these changes would take time and numerous small steps. Every transition always starts with a vision and changing the course of a tanker ship is not something that can be accomplished overnight. While enjoying my delicious birthday meal at the steakhouse ↗ in the heart of Disney Village, I couldn’t quite put my finger on what was bothering me. But I was determined to figure it out, because I knew where I wanted to go.

Like every architectural endeavor, defining an architecture for the next 15 years began with a profound understanding of the current state of affairs: the vision, the goal and the as-is situation.

The Goal

The goal was straightforward: I wanted to find again a position where I could truly focus on “real architecture”, generating business value, ensuring the realisation of the dream of my client, according to best practices and good principles.

Moreover, I wanted to do so during a substantial period of time, allowing me to truly define and execute an architecture as it should be, guiding it throughout its entire life span. I wanted to be part of that bigger story again, conquering architectural challenges as a team.

The As-Is

My as-is situation seemed obvious: I was a solution architect. So I thought. However, as I began searching for my next architectural challenge, I noticed something was off. My response to almost every offered position was that I considered it way too technically inclined. The job descriptions for these architectural positions did not resonate with my view on architecture, especially not my technology agnostic belief. So there had to be something wrong with my view.

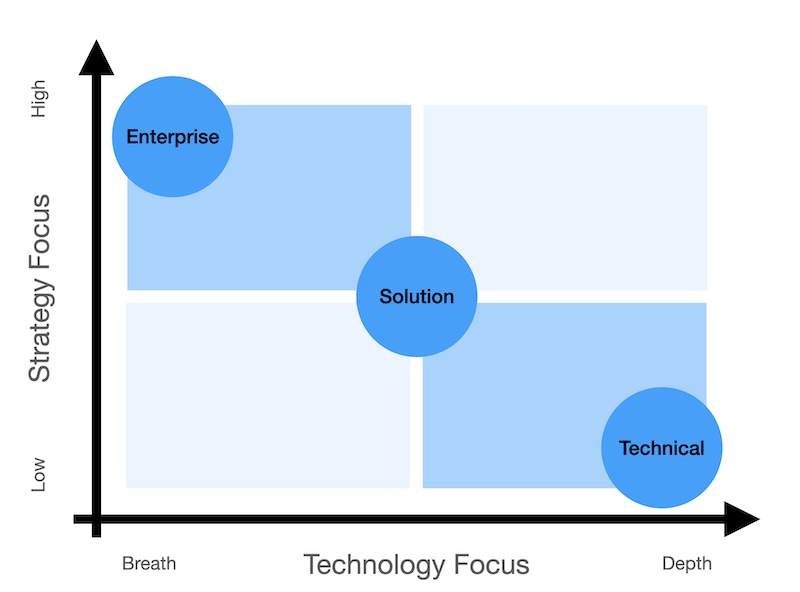

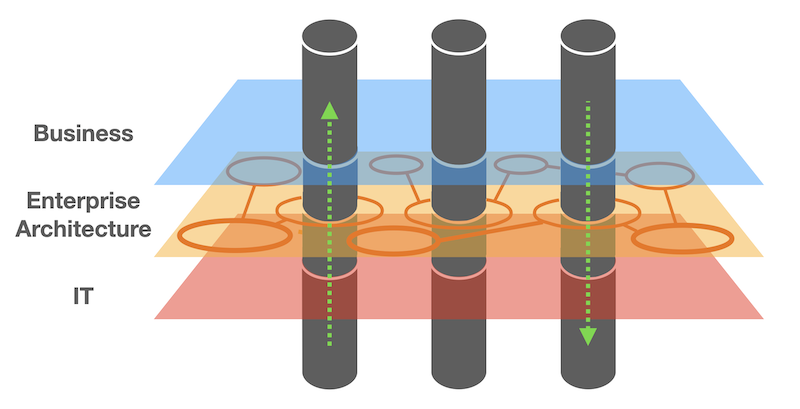

I can’t say who came up first with this simple visualisation, but I stumbled upon it in some LeanIX documentation a long time ago. Since then, I’ve found it to be an good representation of how three crucial levels of architecture are divided among these roles:

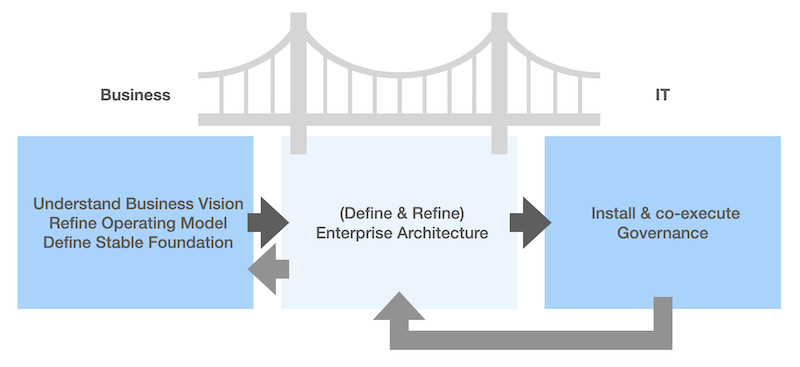

On one hand, Enterprise Architects primarily work at the business or strategic level, ensuring that and organization’s goals are clearly aligned with the IT domain in general. On the other hand, technical architects focus on various technologies, ensuring they are optimally applied in detail.

The bridge between these two domains is the solution architect, who takes the aligned business strategy and translates it into practical solutions. These solutions are constructed from multiple applications and integrations, ensuring they align with the organization’s operations and can be implemented using specific technologies. Solution architects prioritise processes and integration, still working at an abstract level to ensure a seamless translation of business strategy and the creation of tangible business value.

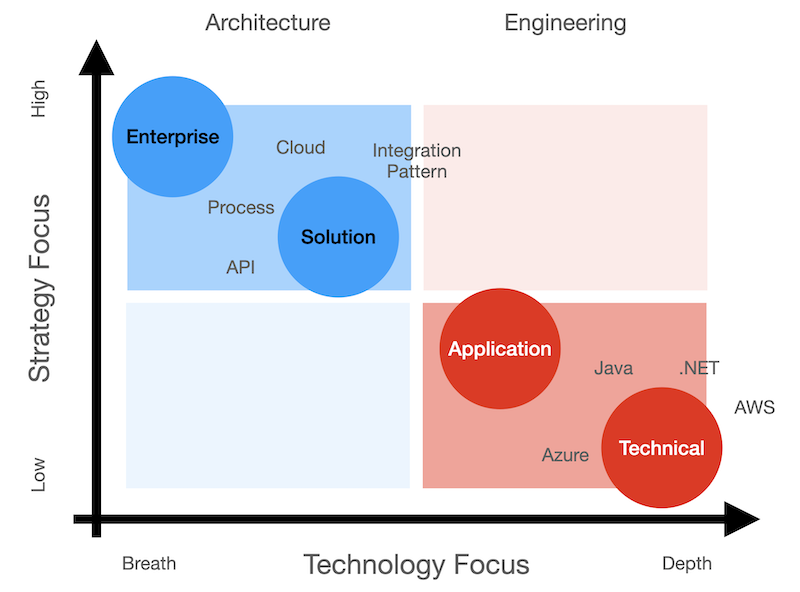

To be completely honest, this is how I think this representation should be interpreted. If I were to draw it, I would add more detail to avoid any misunderstandings. I would even make a clear distinction between architecture and engineering, which, in my opinion, would resolve many of the misinterpretations and the dilution of the term “architect”.

Although I believe solution architects are well depicted as the bridge between strategic and more technical architectural aspects, I’ve always felt that this dual role should be better divided between a solution architect and one or more application architects. This is evident when considering that solutions often consist of a multitude of applications.

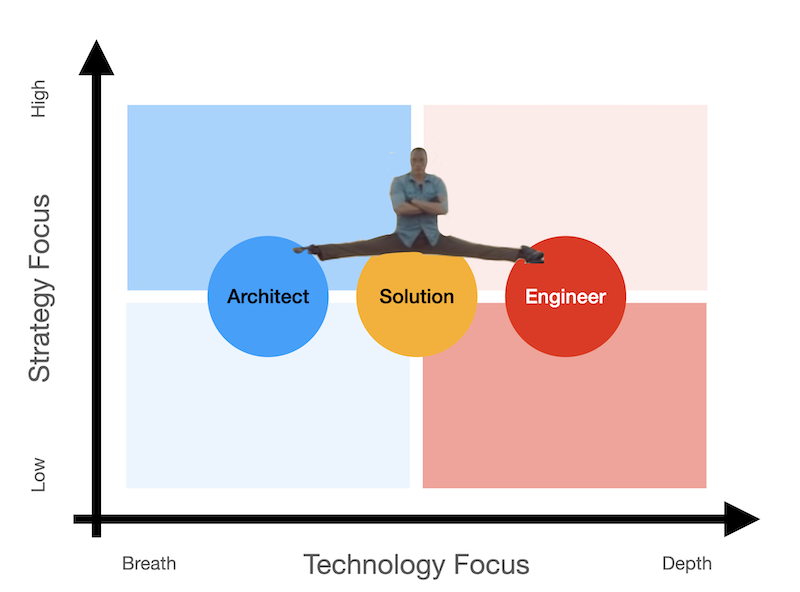

Given the current job market, where solution architects nowadays look more like solution engineers, and my personal perspective on my profession and architecture in general, I can only conclude that I’m currently caught in a painful split between two worlds. It’s time to address this issue and choose my primary allegiance.

The To-Be

That choice seems rather obvious: I firmly believe that the most business value can be realised at the business level, ensuring that the fundamental principles upon which solutions are to be built are well aligned with the IT domain. This should be realised before entering the IT domain itself, thus providing the IT domain with the optimal input to perform its work effectively. In simple terms, my objective is to focus on real architecture — my goal is clear.

Therefore, it’s time to clearly define this architect’s role. This will enable me to outline the necessary steps to make any required changes and fully embrace this role, which is the architect’s way.

A Stable Foundation for Change

Architecture is all about change. It’s about creating something new or taking something and transforming it into something else. People generally resist change. This resistance is deeply ingrained in our nature. Our brains are wired to identify and follow patterns. When faced with change, we tend to find reasons to avoid it, firmly holding onto existing ways. After all, aren’t we often told, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it ↗”?

I can relate to this. For years, I held the title of “software architect”, simply because I identified as an architect, not in the traditional sense of building construction, but in the realm of software. I’ve always considered the distinction between “building” architect and “software” architect clear and simple. Ultimately, the end result is software in some form or another. However, this distinction has become a source of confusion. Recent developments have led me to believe that adopting the title “IT architect” could help alleviate this confusion. This title is more general and focuses on general information and technology, rather than just software. I understand that this may be considered a semantic discussion, but as I mentioned elsewhere, “In the information technology industry, we’re in an eternal naming game.” And some things never change.

So architecture is in fact about people, listening to people, understanding people, their goals and their current situation. It’s about earning trust and using that trust to realize the change people didn’t know they needed or wanted, to actually reach their goals.

It is important to understand that people are driven by their convictions, and these convictions tend to influence their observations rather than the other way around. Consequently, convictions are challenging to change, requiring time and effort. Given this, it becomes more crucial for an architect to invest time in understanding and engaging with people rather than solely focusing on a nice design to persuade them.

If people are change-averse, one way for an architect to move forward and gain trust is to look for stability, typically in the parts of an organisation that don’t really change. Optimising these creates a stable foundation to start from. It builds a level of trust, on which more challenging aspects can be rooted. In that respect, architecture is really about the things that are hard to change.

Change within an organisation must serve its strategy. Change starts with business strategy, by itself the greatest source of change: business strategy is highly volatile, constantly adapting to market fluctuations, seeking opportunities, and making swift decisions across various domains. This very nature makes strategic management unable to predict future changes, but it can identify certain aspects that are unlikely to change. If an architect can digitise these stable elements, management can concentrate on the actual areas of change, relying on a solid foundation for execution. In this manner, such a foundation becomes a foundation for agility. The kind of agility strategic management craves.

A great mental model for this foundation is a car platform ↗. A key success factor is that it should serve multiple business needs, just like a car platform is used in various car models. Given the potential of such a platform, management is motivated to explore innovative ways to leverage it. This increased application of the foundation now enables change to be implemented… through stability.

One final thought about change: before addressing any change, it’s crucial to assess an organization’s readiness for it. Facing change without a adequate common ground will only lead to resistance and opposition. For change to be successful, six essential elements must be present: a clear vision, effective communication, the necessary skills and tools, incentives, and an action plan. If any of these components are lacking, the change process will be challenging and likely result in all too common problems: confusion without a clear vision, rejection of proposed change due to poor communication, fear among employees lacking the required skills, frustration arising from inadequate tools, slow progress without incentives, and chaos when an action plan is absent.

Stability drives Growth

So if stability leads to business agility, it inherently is a driver for growth - or “can be”, because it of course only drives you where you point it to; it won’t and can’t take responsibility for bad destinations. Anyway, growth is another buzz word that rings a bell with organisations’ management. So, taking the stable foundation into account early in the decision making process, might even enforce its weight. Maybe even considering it when structuring the organisation might therefore not be a bad idea. How can we approach that?

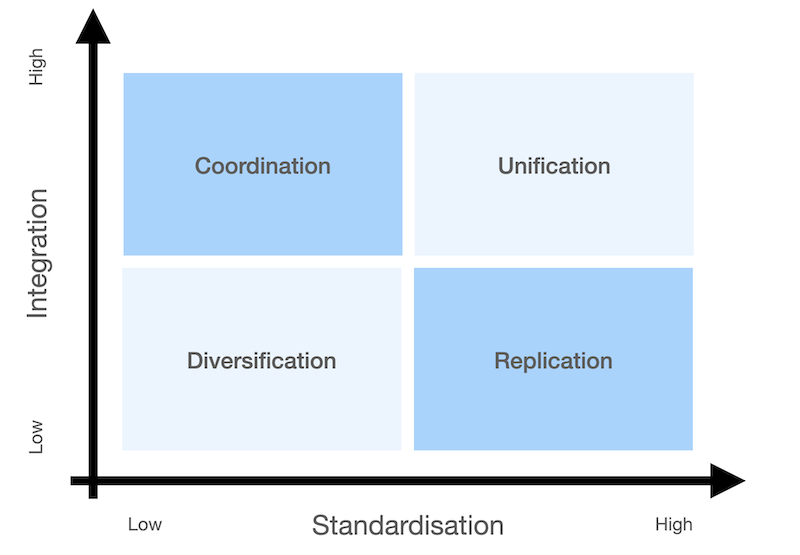

The first step is to agree on an operating model, which basically boils down to a long list of questions that need to be answered: What is important at the core of the organisation to do business? What data is needed by whom? What processes can or can’t be reused? What infrastructure can be shared, or not? If we interprete answers to such questions, we can categorise them along two axis: one considering standardisation and another related to integration. The former deals with sharing of processes (and infrastructure), the latter with sharing of data. “Shared data” is rather abstract, so let’s frame it for now as “knowing about each other customers”, with “each other” being different business units or any other larger entity within the organisation.

Two axis and a categorisation as low or high, leads to 4 simple quadrants, with each objectively identifying the operating model of the entity under scrutiny.

Is it really this simple? Can organisation be categorised in merely 4 large categories when it comes to their operating model, the way they do business at their core? Yes and no. I explicitly started mentioning “entity”. This operating model categorisation can be applied at different levels and might result in different models at those different levels. So depending on the size of the entire organisation, there might be one operating model at the highest level and one or more completely different ones at lower levels. The important aspect of this step is to clearly (and honestly or bravely) identify it.

These four operating models reflect the core of doing business, and therefore how the business strategy resonates considering the axis, which are two major axis with respect to IT, which is after all our final destination. For an architect this is the highest level strategic divide, which will influence many, if not all decisions to come. Here the importance of considering it when structuring the organisation itself. Honestly identifying the operating model and then moving in a different direction doesn’t sound the smartest way to go about it, right? So given an operating model, strategic management should adopt it and live it, to ensure that everything built on top of it benefits from this stable foundation.

How do we interpret these four models? Starting at low integration and low standardisation, we find diversification, which implies that no processes, nor customers are shared across business units (or entities). In general this is a typical operating model for holding-like organisations, that have very distinct business units, with very distinct products and customers that are unique to the products/units.

Organisations that typically benefit from sharing customers (data) across their business units, yet still apply different processes, mostly due to vastly different products, adhere to a coordination style of operating model. In Belgium we have the concept of a “sociaal secretariaat”, they are a layer between the government and organisations, dealing with the handling of collecting taxes on wages. They typically deal with the wages of employees, yet also deal with their managers, who are often self-employed and/or leaders of their own companies. Different business units approach these different “roles”, with different products and services, yet often dealing with the same underlying “person”. As a freelance architect, with my own company, I fall in at least three such categorised roles and when I log on to their portal, I even get the choice as which role I want to identify. At their core, I’m a person, shared across different business units, subscribed to different products and services. In a well-architected world, this would be a great example of the coordination operating model.

Going the other direction, with a focus on reusing processes, while still catering to different customers, we find the replication operating model. This is a well known model in many franchise-like organisations. Simply consider McDonalds: they literally replicate their restaurants to the smallest detail, while serving completely unrelated customers - which is not completely accurate, as one of the motivations for replicating the “quality” of their food across the globe is that wherever you enter a McDonalds restaurent, you get exactly the same experience, which is one driving force for looking for a McDonalds when you are abroad. Still, restaurants don’t share any customer data whatsoever. In recent years, there surely is a shift to be observed here, with the introduction of a McDonalds app, which puts a “customer” overlay across the different restaurants.

Finally, organisations that strive to high standardisation of their processes and heavily share customer data across their business units are following a unification operating model. The prime example of such company is Amazon: they have really standardised every little detail of their operations and share data across all units to create an extremely strong customer intimacy. The only thing that is embedded on this highly unified sales platform is the product, which ranges from the original books, to nowadays about everything you can imagine, all sold and delivered with the same speed, accuracy and overall experience.

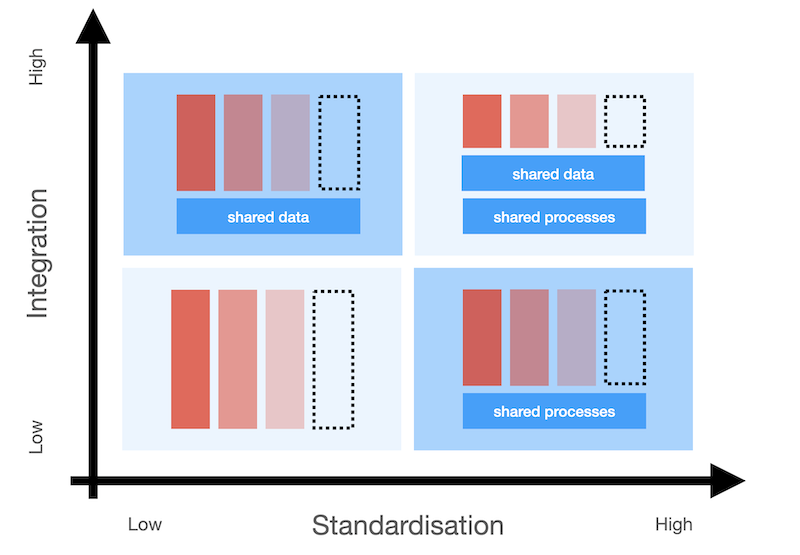

In terms of constructing a stable foundation, each operating model has its typical foundation, with its characteristics, both the things they offer and require.

Where’s infrastructure in all this? Isn’t it equally important and shareable? Absolutely, and it’s even something that can be integrated into any operating model. As we’ll see later, shared infrastructure is one of the initial steps towards maturity. In fact, it could even be considered a precursor to architecture itself, which is a contradiction in itself because infrastructure is technology, and technology is merely the outcome of the formula of architecture. For now, as hinted before, I’ll mostly consider shared infrastructure (or systems) at the same level of shared processes, which often require sharing of infrastructure to realize their own sharing.

Now, do mind that this all still sits purely at the organisation level, dealing with the way business is done at its core. In a way, it’s merely still input for an architect to start from. The next step is to translate this operating model into an Enterprise Architecture, which is basically the digital implementation of the operating model.

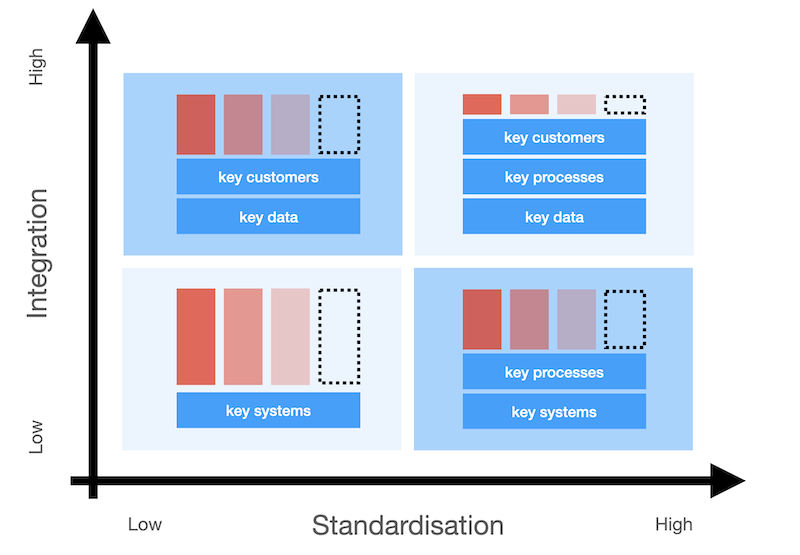

When we transition to the IT domain the two dimensional operating model can be interpreted using four key aspects: key processes, key data, key systems and key customers. Translating the operating model in a focus on these key aspects, brings the next level of profiling of the organisation.

A unification model will typically require high focus on customers, then on processes and finally on data. Unifying systems is less of concern, mostly thanks to the already high unified approach to all other aspects. This is not unexpected. With so much aspects standardised, the ultimate focus of this model should on the only thing that is left to change: the most intimate relation to the customer, an extremely personalised and streamlined interaction, the ultimate user experience.

At the other end of the spectrum, a diversification model will at most focus on key systems, on trying to benefit at the lowest level of integration, ensuring that the most basic technological needs are as efficient as possible, trying to gain a bit at a generic level. Processes, data and customers are all completely different across the units.

The coordination model will again require focus on key customers and also on data, to ensure that all distributed processes are coordinated well through this shared information.

Finally, the replication model will focus on standardising processes and systems, as these are the only things that can be replicated. Sharing data is out of scope since there are no shared customers.

The focus on these key aspects for each operating model, is a path for an architect to identify those aspects that are important and absolutely belong in the stable foundation.

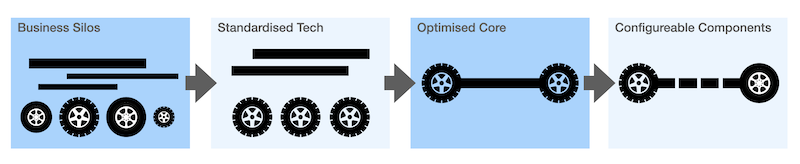

Growth leads to Maturity

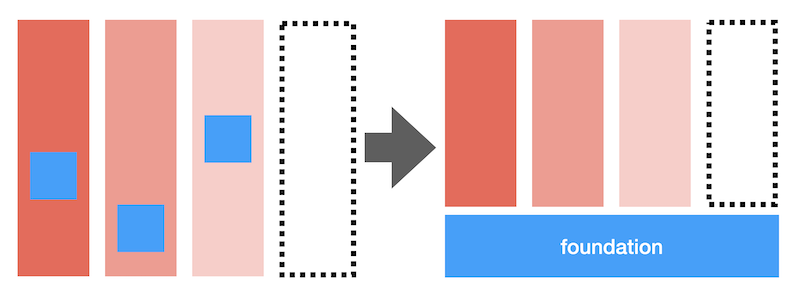

When organisations can grow, thanks to a stable foundation, based on a clear operating model, they also evolve inherently and become more mature. Four phases of maturity are typically observed, starting with isolated business silos, with little or no common ground and every business endeavour results in the creation of almost a complete independant parallel organisation. This is where organisations without a clear view on their operating model and no kind of stable foundation start out.

A typical firs step up the maturity ladder is standardisation of technology. The introduction of shared infrastructure leads to some cost optimisation by itself, yet it is mostly the reduction in choices that make new steps more cost efficient. Organisations at this level of maturity typically also install a CIO, as they subscribe to the need to focus on optimising their IT. Many organisations nowadays are at least at this level. The advent of cloud platforms has undoubtedly been a catalyst for the growth of this level of maturity.

If we now add optimised application of processes and data in the mix - like the ones resulting from a stable foundation - organisations reach the level of an optimised core thanks to their architecture. This is still the focus of the majority of organisations these days.

A final maturity level reaches beyond all the benefits we have already addressed above. By making all components in the stable foundation even more reusable, by making them available as configurable components, the stable foundation becomes almost malleable to even the most disruptive changes

Remember the analogy with the car platform? A the silo level, every new car model would require their own wheels, beams… Standardisation of technology would introduce a single set of wheels and beams for all. With an optimised core, those wheels and beams would be assembled in a single common car platform. The last level of maturity would for example add the possibility to change the length and width of the platform, thus removing any limitations on dimensions, or introduce a choice of wheels.

One could now argue that the best way forward is to take a big leap and come up with all those configurable components, resulting in the most agile organisation of them all. Too bad, it doesn’t work that way. Although the idea is simple, the execution demands experience that can only be learned by taking each of these steps, one at a time. Without standardised tech, nicely implemented at all levels of the organisation, not only technically, but also with all the required education, documentation, support… it is nearly impossible to implement common processes and shared data. Without first having installed shared processes and data, it is again not possible to make those same processes and data configurable. The steps, the changes in between these levels of maturity are just too complex by themselves, that taking one or more in one go will always result in at least sub-optimal outcomes, which will hurt more than when addressing them one at a time.

Aligning business strategy with IT helps ensuring that IT alone doesn’t skip steps, which is easy since IT has a tendency to (over-) abstract and (over-) modularise, often seeing only the ultimate maturity level, easily skipping processes and data from an organisation/business point of view.

Companies become more agile as they move their foundations through the different stages of architecture maturity. A company’s operating model dictates the route it takes to architecture maturity and the benefits it achieves.

An Architect’s Life

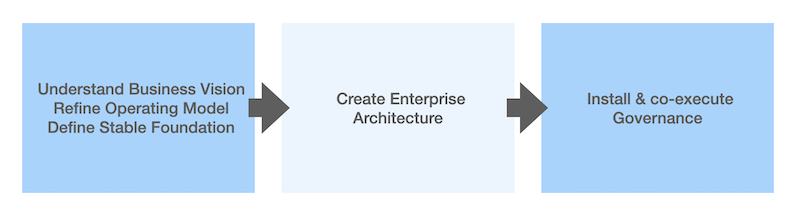

So, I dove right in and we already covered a lot of ground there, mostly at the strategic management level. This is in the end, where it all starts. Yet, this is merely one third of the responsibilities of an architect. Let’s step back for a minute, introduce the entire architecture life cycle and its context, before we move on to the next phases. This will offer us a mental model to start from, to which we can refer back and forth while continuing our trip.

Above we covered phase 1, where as an architect you join the strategic management to understand their vision, give feedback to help refine it into a clear operating model and from that operating model define a stable foundation as a first step towards an actual Enterprise Architecture.

In that first phase, basically, the “dream” is converted into an actual picture, a clear representation of the organisation and its goals. This is the first step towards the alignment that the architect wants to bring across the entire organisation and it starts of course with the direction the organisation wants to go.

Business strategic questions revolve around identifying an organization’s unique assets, leveraging them to create a competitive advantage, and ensuring its long-term sustainability. These questions are often articulated in terms of a mission, which encapsulates the organization’s purpose, a vision, which outlines its goals and objectives, and goals, which describe the steps to take to achieve those objectives. In essence, the overall business strategy.

Note that phase 1 is in a way optional. It is often the case that this phase was already performed in the past and the architect can just build on top of it. Life cycle here doesn’t demand an end-to-end approach, it merely outlines how its phases are sequenced, mostly to indicate what “deliverables” from the previous phase should be present to be able to move forward in sound way.

Phase 2 builds upon the clarity reached in phase 1 and focuses on the construction of an actual Enterprise Architecture. As an architect, you take the mission, vision and goals and prepare for action: defining more concrete objectives and initiatives to target those objectives. In addition, measures and targets are defined to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation.

This might seem as a straightforward task, yet it requires a lot of experience and creativity. Good architects are like chess players and can identify enough possible outcomes, identifying bad ones, and choose one wisely. It requires also a lot of forecasting and backcasting to anticipate on future needs, taking just enough into account today. Since architecture deals with the stable parts, it spans longer periods than business and has to be able to adapt to this strategic agility.

An Enterprise Architecture aligns the business strategy to an IT strategy and typically includes the as-is, the vision, how to get there, key strategies, a plan, implementation steps, responsibilities & resources, targets, resource constrains and review points.

And it doesn’t stop there. Phase 3 might very well be the most important one. As an architect you don’t simply present your architecture; you execute it, explaining the architecture, its underlying principles, and the reasons behind them. You not only install policies and frameworks to guide the implementation process, yet also monitor it, establishing governance mechanisms to ensure adherence to principles and validating technological choices and development practices.

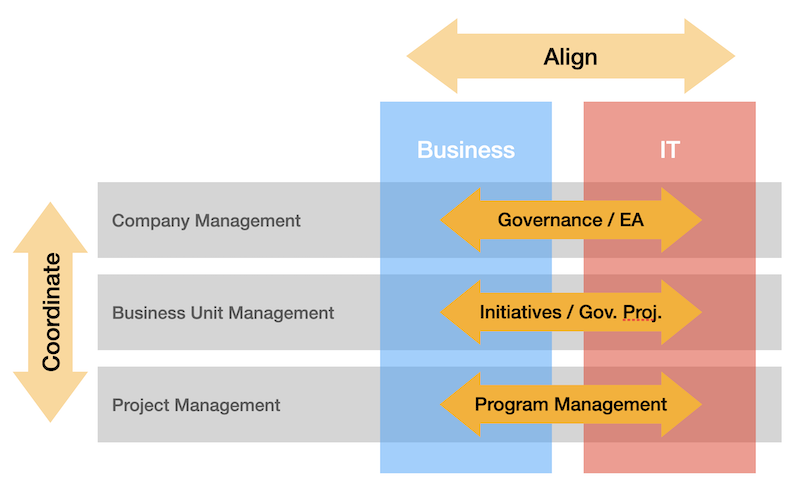

And even more important than the active aspects of the governance phase is the collection and incorporation of feedback from phase 3 into the architecture and the feedback loop to the strategic management. Adding those in the picture we can observe the proverbial bridge that an Enterprise Architecture creates for the alignment of business and IT.

This really puts the architect in the middle of many of the activities surrounding the implementation of the business strategy. With respect to innovation and R&D, an architect follows up on the technology watch and ensures everything remains aligned to the vision. While planning, the architect incorporates feedback in all blueprints and aligns the corporate portfolio and roadmap. During building, he guides and follows-up on progress, measuring it as objectively as possible, reporting back the findings. Finally, while running the implementation, the architect keeps track of the application lifecycle management.

The Enterprise Architecture Compass

During the first phase, in his strategy oriented role, an architect has worked with management to clearly define the vision and goals, embedding them in a matching stable foundation. This by itself is still miles away from any implementation in the IT domain. We’re only at one end of the bridge and we need to cross it to reach the IT domain.

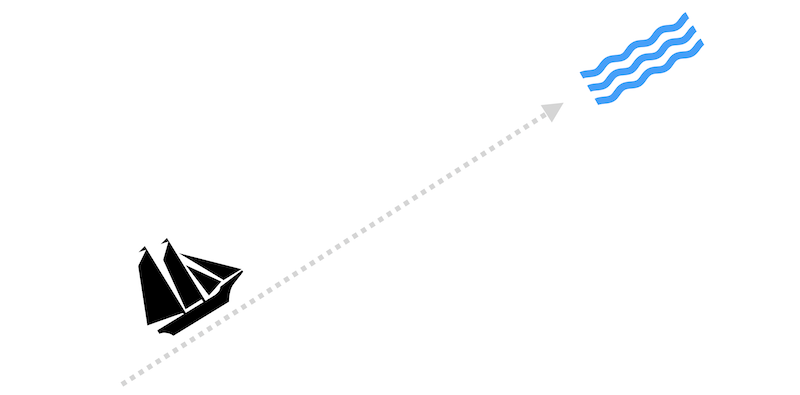

The bridge we need is the Enterprise Architecture. And although the bridge is a nice metaphor, let’s introduce another one, one that more clearly illustrates the fundamental importance of Enterprise Architecture and what sets it apart from simply implementing business goals as-is in the IT domain.

Allow me to take you under the bridge, onto the water and introduce you to another passion of mine: Sailing

It’s a common misconception that wind propels a sailing vessel forward. In reality, it’s the opposite; the wind actually pulls the vessel forward. Just as the wings of a plane are pulled upwards due to aerodynamics, the sails of a vessel are also pulled forward by the same physics forces. This enables a ship to steer in almost every direction, except directly into the wind.

Many projects in the IT domain often feel like sailing straight into the wind. It simply is not possible and results mostly in overbudget and overtime frustrations of everyone involved.

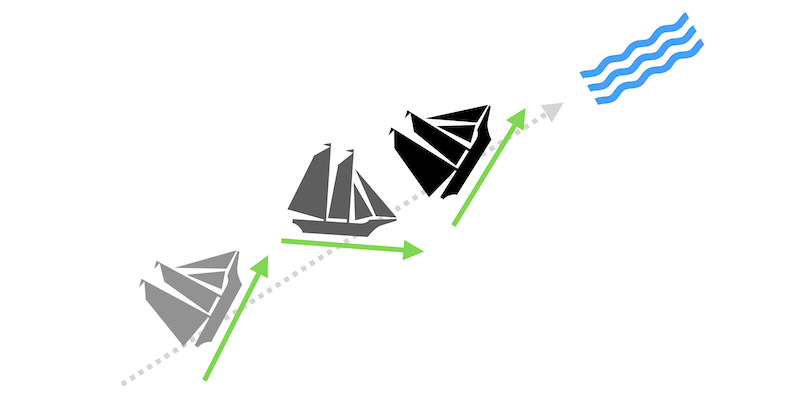

Luckily, captains have a technique at their disposal that allows them to still set course to the destination straight into the wind: “beating to windward”. In stead of setting a direct course, beating to windward chooses courses that are slightly off and alternates them, while tacking ↗.

Enterprise Architecture is most of time exactly the same: as a compass, it points in the right direction, towards the business vision, still it takes a captain, an architect, to plot the courses to intermediate destinations, to reach that final destination. And although this may seem to incur additional costs, in the long run reaching the goals with those additional costs, will cost a lot less than not reaching them at all. Practically, by asking a basic question “So what (if we take this hit)?”, by making the cost ultra concrete and explicit, the fact of making an apparently slightly off-course tack, is most of the time easily considered the best way forward.

Constructing the Enterprise Architecture

Is it a blueprint? Is is a model? Is it a business case? Is it an analysis? Is it…? No, it’s an Enterprise Architecture and it encompasses all of the above.

If you got the impression from the analogy of the compass, that an Enterprise Architecture is “simply pointing” in the right direction, I’m sorry, I’ve mislead you. An Enterprise Architecture, including the intermediate destinations, plotted by the captain/architect, is a living document that encompasses many things and takes into account even more.

A succesful Enterprise Architecture…

-

…should be clear, must be specific and be constituted of actionable objectives.

-

…has to provide motivation how it meets company goals.

-

…ensures its autority, by providing the needed enforcements.

-

…implements early intervention and prevention mechanisms.

-

…welcomes and incorporates feedback, which can only be embedded in transparent 2-way communication

That mostly describes the what and how. The most important question though is “Why?”. What benefits does setting up an Enterprise Architecture bring for an organisation? At the strategic level, we’ve already hinted at the support it can bring in (re)defining the strategic vision and goals, as to enable a smoother transition to the IT domain. Here now is a list of 10 topics that an Enterprise Architecture offers organisations:

- a shared vision for the entire organisation through alignment

- reduced complexity

- reduced costs

- reduced risks

- improved collaboration

- improved alignment of investments & resources to business strategy

- improved compliance

- improved organisational resilience

- improved system interoperability

- standardised practices and processes

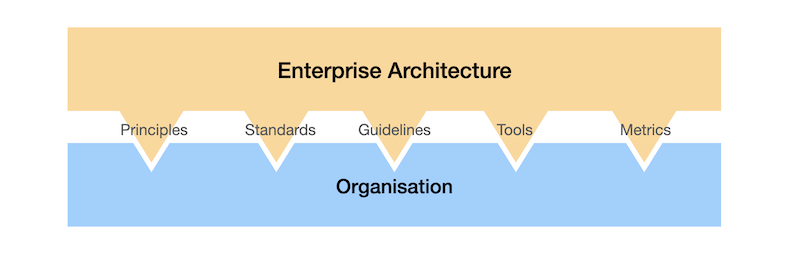

To be able to deliver on these benefits, an Enterprise Architecture provides a plethora of support to the organisation in the form of principles, standards, policies, models, metrics, processes & procedures… It is essentially an elaborate insurance that locks the organisation in an as objective as possible and well thought through supporting framework, fully in line with and based on the refined business strategy and goals.

The Architects Coven

We’ve identified how an Enterprise Architecture supports and locks in an organisation. Let’s now briefly look at this picture from a human perspective. The Enterprise Architecture isn’t simply something that a single person comes up with. It’s the assembly of the work of possibly one, but most of the time a team of architects, each with their own specialty, adding viewpoints from their perspective, all accumulating to the overall Enterprise Architecture.

There are three fundamental types of architects: Enterprise, Business, and Data. A quick overview of their responsibilities highlights how they collaborate effectively:

Enterprise Architect

The Enterprise Architect essentially is responsible for the Enterprise Architecture. Responsible doesn’t mean he has to do everything himself. He relies on the Business and Data Architects to bring their expertise to the table, further adding detail to the overall picture he already painted.

The Enterprise Architect is foremost the single point of contact regarding the Enterprise Architecture and kicks off the architectural work with the strategic management, as we saw above. At the other end of the spectrum of his role, he will ensure that the realisation of the architecture is done according to best practices and good principles, as defined in the architecture.

Core responsibilities:

- identify domains vs business units

- manage the business capability map

- distribute and consolidate all other architects’ work

- as-is and to-be projections + selection of the best combinations

- construct a high level roadmap

Business Architect

Although the Enterprise Architect needs a deep understanding of the business and its vision, the Business Architect will take this vision and dive much deeper into the details, ensuring that the high level strategic views are also valid for all actual cases. Where the Enterprise Architect guides, the Business Architect leads.

Core responsibilities:

- business processes

- business transformation

- business alignment

- business liaison

- bridges between business domains

Data Architect

Partly as an outpost, on one hand on the border of technology, and on another actually at the core of everything, data is both as concrete and abstract at the same time. Where the Enterprise Architect deals with the high level data concepts and entities, the Data Architect will, just like the Business Architect, take these concepts and dive much deeper into the details, ensuring that the high level strategic views are also valid for all actual cases. Where the Enterprise Architect guides, the Data Architects leads.

Core responsibilities:

- formal data structures, descriptions, designs

- involved in selection of systems

And What About…?

You might be missing (at least) two other well-known architect types. You might wonder why I don’t include for example Solution and Application Architects. In the introduction, I’ve already talked about this issue I have with these roles, especially with the role that I have taken on over the past few years, mostly by name: the Solution Architect.

This whole thing is basically the reason and motivation why I believe that these roles would vastly benefit from a rebranding as Solution Engineer and Application Engineer and continue a much clearer life within the IT domain.

For the Application this is so clear when looking at its core responsibilities:

- target systems architectures + roadmap

- hard/software requirements

- migration/deployment scenarios

- supervise tech part of tool selection

- monitor actual implementation

Every bullet deals with concrete and technical aspects. That’s engineering. That’s an Application Engineer.

In case of the Solution Architect, who practically overlaps all other architects, including the Application Engineers, it’s problematic. There is a clear evolution to a much more technologically inclined realisation of the role, where I firmly believe it should be technology agnostic. But you can’t argue with reality, so if this glue-role is forced to be technologically focused, it also has to take on the correct name and become a Solution Engineer, operating within the IT domain, working with the Architects and other Engineers, overseeing solutions, comprised of different applications, with an enormous focus on integration and interactions at a process level.

IMHO 😇

From Strategy to Portfolio

We left the strategic phase with a clearer understanding of the management vision, an agreed operation model and a definition of a stable foundation that supports it. These are all still abstract artefacts and these need to be made concrete in a portfolio.

A strategy is about an organisation’s goals, it’s the value proposition, both concerning the product and the market. It’s all about business. To make this more tangible, an Enterprise Architect creates a corporate blueprint. A typical format for such blueprint is a business capability map, which describes the organisation in terms of its explicit capabilities: people, processes, information and IT.

No matter how you look at it, people make (or break) an organisation. Their competences are important, and also how the organisation is structured. People work together in a certain way. Processes describe this way of working and visualize how the organisation operates. Every process needs and produces information of some sort. It is of utter importance to know if we have all the required information and if it is complete, accessible and secure. Finally, this information is handled by some sort of technology. Does the IT match all of the above?

I can’t stress this enough: The corporate blueprint or capability map is not the plan itself, it’s the template onto which the entire Enterprise Architecture can be drawn, by projecting different viewpoints onto it. In that way the business capability map serves as a structural blueprint.

Examples of such viewpoints are the current tech landscape, the future tech landscape, risks, opportunities, impact analysis, expected savings vs costs, expected efficiency gain, integration points… Corporate drivers can also be viewpoints that when projected onto the capability map can bring clarity: customer focus, compliance mandates, mergers & acquisitions, at-risk projects, decision making in general, operational excellence…

By using the same underlying map for each of these, synergy between completely different viewpoints is realised and cross-cutting concerns can be identified at the abstract level of the map. These concerns can almost literally channel information from the strategic level to the IT level and back, based on a shared language as embedded in the architecture.

These cross-cutting concerns can then be used to formulate programs and projects to realize these concerns, or moreover the transformation of a given state to a new one. These programs and projects are the tangible building blocks of the evolution that the Enterprise Architect aims to realize, the pieces on its chess board.

The inherent duality in a portfolio of programs and projects answers to this quest to align business and IT. A portfolio is the sum of all (business) programs. These result in business-centric outcomes. One such program by itself is the sum of a series of projects that rely on, yet also define, the identified capabilities.

I admit, I’m not a big fan of extensive and elaborate management frameworks, yet there are absolutely nice aspects to be found (it probably also takes a captain to navigate through these 😇). COBIT 5 ↗ is an overarching business and management framework for governance and management of enterprise IT. It relies on 5 core principles when essentially setting up an Enterprise Architecture. I always felt that my mental model, as presented above, aligned nicely with these:

- meeting stakeholders’ needs

- covering the organisation end to end

- applying a single integrated approach

- enabling an holistic approach

- separating management and governance

Starting from the business vision, materialising it as a portfolio of business programs is clearly focused on “meeting (business) stakeholders’ need”, while managing the translation to projects clearly supports “meeting (IT) stakeholders’ needs”. Fundamentally tying together business and IT through a solid up/down channeling architecture, takes “covering the organisation end to end” at heart. The creation and management of a portfolio embodies “applying a single integrated approach”. At the same time, aligning programs and projects strives to still “enabling an holistic approach”. And finally, although the focus is clearly on channeling throughout the organisation end to end, those same channels or architecture also allow for separating management and governance”, each relying on and serving a different party.

Now, if a portfolio is the tangible or rather instrumental tool to steer the realisation of the management vision, how can an architect actually construct this from rather abstract foundations, such as a capability map?

Money, Money, Money…

Although it’s a very simplified and almost dumbed down statement, still it serves well as a starting point. Architecture helps to optimize cost. One needs to consider this along the same lines as an accountant, who - if he does his job well - helps in reducing costs and in that way repays his own cost. Likewise one can see Enterprise Architecture as repaying its own cost and more by solving complex holistic problems at a high level, where the impact when it trickles down becomes larger and larger, much like a snow ball rolling down the hill getting bigger an bigger. Another way of looking at this is, is the idea that an architect tries to avoid costs before they are incurred by IT.

I’ve often used the following very simple and very school-like and ultra-tangible example to illustrate this. Consider a webshop and the possibility for a customer to consult its orders. When addressing this in an operational modus, it all seems very simple: create an account, keep copy of the orders,… all very simple. Now if we consider how customers actually access their orders, in a very high percentage of the cases, they go to their mailbox (which is basically their archive and todo list) and they click on the link we provided to our website to consult their order. If the customer isn’t authenticated, he has to do so, which is once again a hoop he has to jump through. A better approach is to generate a unique and random order number and use that as part of the URL, basically as a shared secret. Logging is no longer needed.

Remember that an architect first of all gains an in depth understanding of the core business, the correct operating model and the key focus topics? From that knowledge the way customers interact with the products and their orders, would for example result in the simple (technical) strategy as state above. The example is of course way to technical, and IT would solve this correctly in most cases nowadays, yet the principle holds.

So the general idea of preemptively optimising cost already clearly shows why thinking about the capability before any applications, services,… are introduced, is valid. Yet, the purpose touches upon some other important aspects.

Dealing with a fragmented (legacy) landscape, consisting both of manual and automated processes, is something that cannot be done at a detailed/application level. It involves addressing the changes that are core to the role of Enterprise Architecture. The purpose of architecture here is to define and explain the targeted integrated environment. It can do so, because it has first looked at all aspects in conjunction from all possible different angles, and only then contextual channels, domains, application groups have been identified.

The primary goal of such integrated environment is of course supporting the delivery of the business strategy. And even in this primary goal, the fundamental cornerstone of architecture reappears: it tries to make this targeted environment inherently more resilient and responsive to future change, thus addressing the future change aspect, in a way avoiding future costs.

One very simple example here is a thorough vision on the evolution of used technologies. An architect will always be a responsible opponent of using the latest and greatest technology. In doing so, future changes are often already incorporated in even the newest projects. Choosing a stable base can often be more beneficial in the long run, avoiding reimplementation due to even newer technological advances. Remember: business value is hardly ever realised thanks to technology. Wise application of technology can create business value. This is the fundamental reason why I consider being technology agnostic a virtue, especially as an architect.

How Much?

Cost is not only an easy-to-sell approach for Enterprise Architecture but also a responsible and safe initial guide. Just as an architect can rely on proven frameworks to make choices about operations, they can also rely on proven frameworks to make choices about cost.

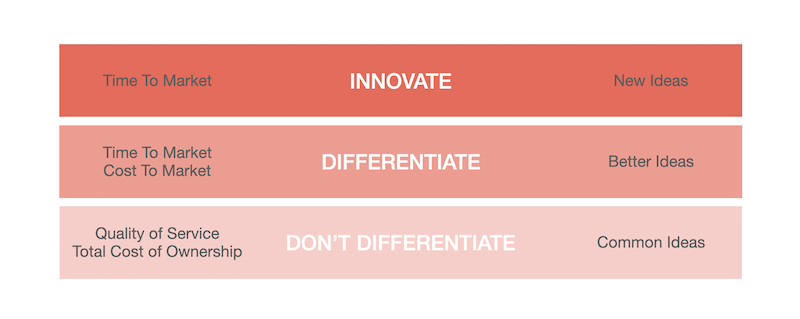

Take for example the Gartner Pace Layering Strategy ↗, which “is Gartner’s methodology for categorizing, selecting, managing and governing applications to support business change, differentiation and innovation”. Go ahead and read more about it. I’ve distilled a handy tool to guide cost-related decisions, particularly with regards to technology choices, which inherently dictate costs and also risks associated with them.

It comes as no surprise that choosing state of the art, innovative technologies, products and services comes at a cost. It’s new, it often lacks experience, which needs to be gained on the job, sometimes in the near future it goes out of fashion. So from an architecture point of view, you should only choose to innovate when time to market is the only primary business driver. If you have a business opportunity, where you can (and want to) be the first and only player on the market, the cost of innovative technology can be validly applied. New ideas require new technologies.

Artificial Intelligence is such a prime example these days in 2025. Most businesses and business cases don’t justify the exploratory use of AI - still everybody loves a good hype cycle 😇 and everybody is jumping on the bandwagon. Let’s see where this leads us.

When there is no value to be on the market first, yet there is still value in being part of a blooming one, both time to market and cost to market come into play. There’s an urge to differentiate ourselves from others, but we should also consider the cost of participation. Better ideas often require customisable standards.

There is a whole market segment focussing on these type of business situations. This is where SaaS platforms have found their territory. Two market leaders in this field of almost-ready-to-use-yet-still-customisable platforms are ServiceNow ↗ and Microsoft Dynamics 365 ↗. They offer a budget-friendly, state of the art set of integrated solutions, that still allow for customisation and tailoring to create a differentiating experience for customers,…

On the entirely other side of the spectrum, when business drivers are quality of service and total cost of ownership, it is clear for architecture that proven non-differentiating technologies and products should be tapped into. There is no gain to find in bleeding edge technology, which risks outages or mistakes, when business wants to deliver a stable and solid services to its customers. Common ideas require proven standards, benefitting from all they offer.

Installing a helpdesk or support system typically falls in this category and benefits from proven customer-facing solutions. Critical master data is another prime example. This is no place to start experimenting.

The fun part I’ve experienced a few times is that this strategy can also be turned upside down. If business defines its drivers in terms of the urge to innovate, choices can be made with a time to market focus, when management wants to address an opportunity with a differentiation strategy, both time to market and cost to market will drive architectural choices and so on.

Identifying the pacing of applications and/or components is already a significant advantage in objectifying architectural choices. The pace categories also inherently dictate other crucial choices in the same objective manner.

Innovation occurs rapidly, with unexpected twists and turns. Therefore, it necessitates a flexible and swift governance structure. Conversely, non-differentiating systems require tighter controls, clear change and extensive stakeholder management. Since different systems necessitate varying pacing, they also benefit from different governance styles. By explicitly stating this, we can ensure better integration of these systems at a process level.

Technologically, integration also extends across pacing layers. A key success factor in managing these systems operating and evolving at distinct paces is focusing on bridging the gap between them.

Well-founded integrations also help when systems evolve. As systems evolve, they often outgrow their pacing layer. Today’s innovative systems can become the differentiating and even non-differentiating systems of tomorrow.

Going All-In

Cost is only one angle to approach an architecture. It is even merely one kind of risk that an organisation faces and would like to be protected from by a stable foundation and architectural plan. Cost is more general a financial risk, which means there is a chance that actual money is lost, at least more of it than it should be. In general we can distinguish four types of risk:

- financial

- operational

- strategic

- compliance.

Operational risk entails the possibility that the organisation looses due to failed processes or external factors such as an … epidemic anyone? Strategic risk includes all situations where business isn’t happening as planned. Here also again internal and external factors play their part, with customers’ changing preferences or simply bad managerial choices. A special case of an external risk type is compliance. Changing legislation, or simply violating existing legislation in the broadest sense, can impact an organisation’s reputation and indirectly financial position.

It is clear from this high level overview, that risks are important enough to be included in an architecture. The minimal approach should at least be to do a thorough risk assessment of the proposed architecture. An architect has proven strategies at his disposal to assess risks, thus enabling him to objectively address them in the architecture, as an integral part of it.

Risk Assessment

A risk assessment has two major phases: first risks needs to be identified, after which they can be estimated. Identification of risks doesn’t simply produce a list of possible risks, it provides a categorised list of clearly defined assets that are at risk, to which extend and, in case that the risk evolves in an actual problem, what the consequences are. Only with risks defined up to that level, estimation can be performed in an objective way.

Assets

To identify risks to that level, the first step is to list all assets. Assets is a very broad concept in this context. It includes for example information, money and financial information in general, yet also people, intellectual property, services… Everything that has some value to the organisation, its people or any aspect of it, is an asset that might be at risk.

Threats

“Might be at risk”. Not every asset is actually at risk. So for every asset, the possible threats need to be identified. These can be external or internal, and they are only in a small percentage represented by hackers. External threats include for example theft, sabotage, terrorism, fire, hardware faults, weather, disease…, while internal threats relate to personel with errors, new technologies that introduce problems, theft or the simple fact that personel sometimes simply leaves…

Controls

Having identified the threats is still only half the story. Threats again aren’t absolute. Most organisations will already have some form of control in place. So listing which controls are in place for every asset, allows us to identify the possible gap between threats and controls, which are the vulnerabilities that could actually lead to problems if they are exploited.

Controls come in many shapes, forms, sizes, even colors. They typically vary from some level of advisory to full on blocking. The following table gives an overview of six levels of control and an illustrative example to make them more concrete:

| Level of Control | Example |

|---|---|

| compensating | 2FA (because simple access control is not enough) |

| corrective | backups allow to reinstate a lost situation |

| detective | audit trails enable post-factum investigation of what happened |

| deterrent | warning signs try to avoid problems by informing |

| directive | education is a structural approach to implementing safe guards, like security awareness |

| preventive | access control |

Consequences

Finally, if exploited, not all assets lead to the same catastrophic consequences. For each asset/vulnerability pair, we need to assess the actual consequences. Only when we reach this list will we have a comprehensive overview of the actual risks represented by their consequences, which the organization faces at a specific moment in time.

Estimations

And even now, not all consequences are worth shielding from. Here estimation comes into play. Very bluntly stated: sometimes the cost to protect something doesn’t merit the consequences.

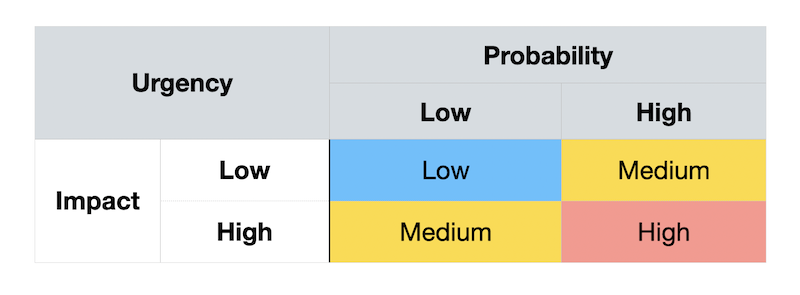

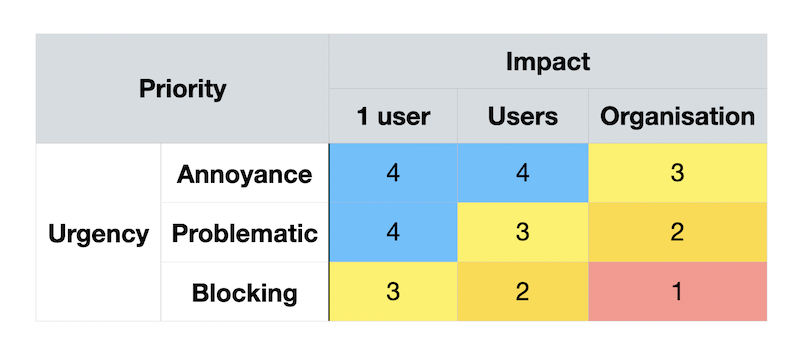

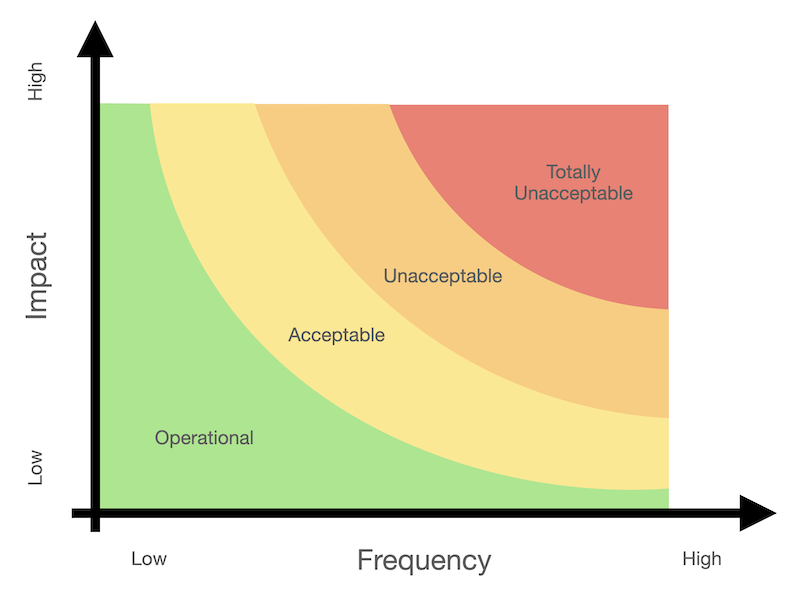

When estimating, aspects such as probability and impact are important, to try and also make this estimation as objective as possible. Organisations can’t simply plug all holes and need to make choices regarding which vulnerabilities to address and with what urgency. There are many simple decision tables that can help to objectify this. Below are two classic ones. They aren’t rocket science, still I can’t count the situations where not using any of such tools resulted in (wrong) guestimations.

Another factor that can be taken into account is frequency. Something that happens once versus something that happens often might require a completely different focus, especially in combination with the impact.

Even with almost objective estimation in place, the result of this risk assessment still isn’t absolute. Depending on an organisations’ risk appetite and risk tolerance, the actual response can be completely different. Risk appetite is an indication how much risk an organisation is willing to take, in general. This is highly depending on the organisation, its management and the context, and it differs from organisation to organisation. Risk tolerance on the other hand defines how much risk is acceptable with each individual risk. The former is in general, the latter deals with specific cases. Note that in literature, these terms aren’t well defined across authors. I’ve seen definitions stating exactly the opposite 🙄

Responses

Risk isn’t only about avoiding, it’s also about dealing with the consequences, when the risk becomes a reality. Depending on the entire analysis so far, we can also describe how we will address the reality as it unfolds.

Responses can range from taking measures to avoid or terminate the consequences, to transferring them to a third party for handling, to simple threat control and reduction, up to simply accepting the risk and its consequences, choosing to mitigate the problems, or simply tolerating it.

But there is More…

Cost and risks in general are interesting viewpoints to address in an architecture. They have a very clear and direct link to day-to-day managerial viewpoints. But there is more…

Let’s briefly recap that architecture provides a bridge between an organisation’s business goals and its IT capabilities: technology, information, business processes and governance.

This bridge or integration of business and IT offers a great platform, holding a lot of opportunities for an organisation. The gathered information and the objective way of looking at all aspects of an organisation, offers access to improved operational efficiency, enhanced innovation and greater adaptability to market changes.

Looking specifically at operational efficiency, architecture enables streamlining business processes, e.g. by reducing redundant activities, offers enhanced visibility into organisational risk and improved resource allocation aligning with strategic priorities.

As a direct result of improved operational excellence, as well as a consequence of a high degree of process and capability mapping in general, an architecture can help in increasing responsiveness, creating more customer intimacy, which is nothing less than a direct business impact.

With well defined knowledge about technological innovation, product leadership can be augmented, allowing to be first on new markets, responding to opportunities, bringing more strategic agility to the management table.

All these benefits are all a result from introducing Enterprise Architecture with an initial focus on the strategic level, and we haven’t crossed the chasm to the IT domain yet…

Crossing the Bridge

So far we have mostly covered the high level, business-oriented aspects of architecture and how architects support strategic management in fine tuning their strategy, creating an IT strategy.

Now, a strategy is merely a strategy, until it gets executed. To bring an IT strategy to reality, the architect needs to give as much attention to the IT domain as up to now to the strategic managerial realm. Yes, business value is key, yet at one point, the vision needs to be translated to an actual implementation, using concrete technology, dealing with real-world issues and it all has to be done by humans. If you believed that defining an operating model, creating a stable foundation and setting up an Enterprise Architecture were though, then please take a peek at the other side of the bridge. We’ve only just begun.

Architecture within Organisations

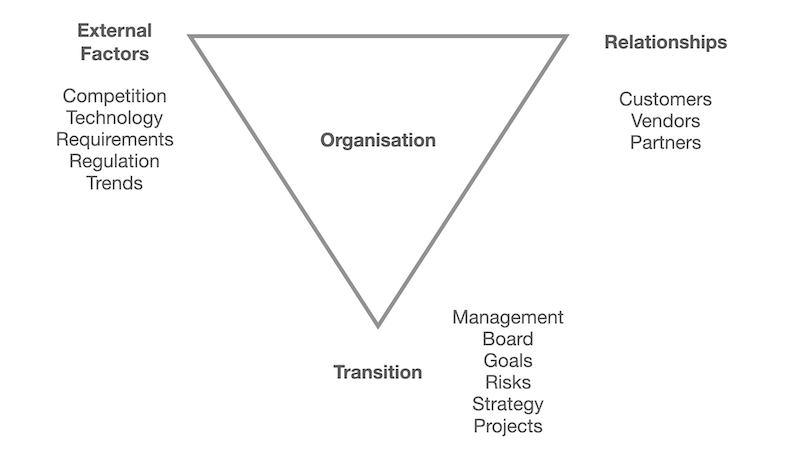

While looking at the role an architect plays at the strategic management level, we touched upon several aspects that organisations deal with. All of these are of importance for the architect to take into consideration. They can be categorised into three major categories: external factors, relationships and transition.

External factors include of course competition, but also simply technology is an external factor; requirements and regulation are things an organisation has to keep an eye on and even trends influence how an organisation should and can proceed. Some of these are semi-predictable, some of them are always a surprise.

Relationships consist of customers, vendors and partners.

Transition groups all aspects related to running the actual organisation, which in the end is a constant stream of transitions, bringing the organisation from one goal to the next, typically… under influence of the two former groups. It includes management itself, the board, goals, risks, strategy, projects…

The Enterprise Architecture captures these aspects in a collection of models dealing with processes, the organisation as structural whole, governance, risk & compliance (commonly referred to as GRC), capabilities, topology… This is all a direct result from the in depth analysis at the business/strategic level.

If we look at how architecture deals with other parts of an organisation, we see that its main focus is on executing an ensuring everything that has been realised so far. While at the strategic level the focus is on the long term, on the roadmap with strategic goals being translated into initiatives, in line with market focus, we see a different focus when dealing with programme management and business as usual IT.

When working with programme management, architects focus on the shorter term translation of the long term roadmap. Remember the analogy with the compass, the captain and especially the beating to windward?! Well, here, the captain looks at even more and smaller tacks to reach his goal, and those even smaller intermediate targets may seem sometimes even counterintuitive, they do fit in a much bigger picture. This is also the reason why a strong focus on the coordination of integrations is key at this level. Other important supporting focus lies with looking after the management of risks and on the ultimate goals and the costs.

While programme management typically drives the transition of the organisation, no organisation escapes the curse of business as usual. Here the architect will again take a long term vision under consideration to support and guide choices to be made. He will help setting up specific architectures for this kind of IT endeavours, all to ensure that also these activities stay aligned with the overall vision.

Let’s stress this once more: architecture does not, doesn’t want to and doesn’t need to step on anybody else’s turf. An architect never directs how IT should do their work. Architecture is by no means IT (and vice versa). Architecture outlines the business dream/vision/strategy and sets boundaries for IT to flourish within, ensuring that IT/it stays inline with the business strategy. It will recommend, it will follow-up, it will monitor and mentor where possible, but it will never overrule, replace or kill IT in any way.

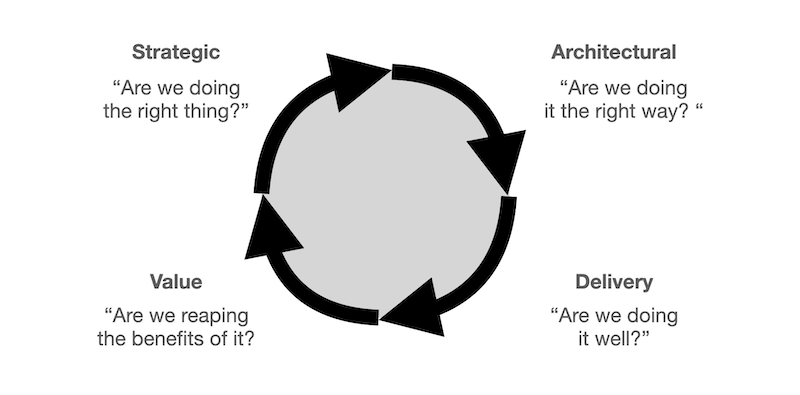

I once saw a very nice summary of the way architects drive different stages of an organisation forward, by formulating the right questions. It illustrates beautifully how the architect can drive the ever iterating cycles throughout the organisation, ensuring that the organisation stays on course at all times.

At the strategy phase, asking if we’re doing the right things clearly focusses on vision, goals and balancing value, cost and risk. It finds closure in the value phase, where we question if we get the actual benefits we were after in the first place. Is everything clear, how do we effectively progress, is it all still relevant and how about accountability?

The Architecture phase focuses on how things should be done and seeks answers to the question if we’re doing things in the right way. Is everything in line with the business strategy, are we being consistent? The delivery phase focusses on getting things done and asks if we’re doing it well. Are we effective, do we have the required capabilities?

The upper half of the diagram is the strategic/architectural domain, the lower half is the IT domain. Fun fact, some authors call the upper half the business domain, and the lower half the solution domain. The business domain deals mostly with the “what”, while the solution domain deals with the “how”. I can only concur, and it reinforces my view on the solution engineer. The architect cycles through both halfs, supporting each phase, guiding, monitoring, refining, pretty much like a catalyst.

At the strategic level, the architect also has to face a few questions coming from the business side itself. The architect might ask if we’re doing the right thing, but his business partners will ask him if it will work, or what it will mean for the business, or what it will mean for the person himself. Remember: people are change-averse and will question everything to avoid change. So each architectural question might seem simple in itself, there are a lot of counter-questions challenging it even more.

Governance

… is the overall complex system or framework of processes, functions, structures, rules, laws and norms born out of the relationships, interactions, power dynamics and communication within an organised group of individuals. (Wikipedia ↗)

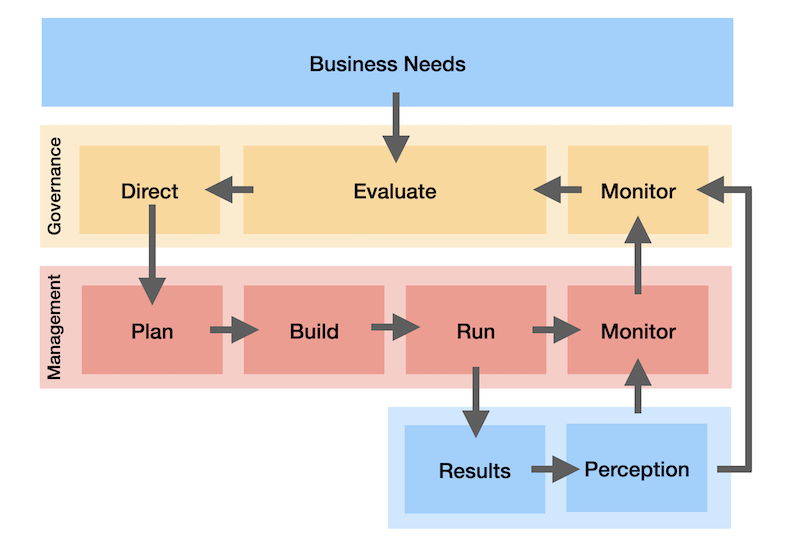

Crossing the bridge means bringing the architecture to the IT domain. To do so successfully, the architect not only has to provide the architecture, he will also have to explain it, motivate it, in short execute it to the fullest. And even that is not enough. He will also support and monitor the execution throughout every step. He will install a complete governance, consisting of processes and functions, structures and rules, laws and norms, all as a direct result of the strategic phase that came before it, while taking into account the relationships, interactions, dynamics and communications within the entire organisation, and thus also including the IT domain. The following diagram offers a schematic overview of an organisation with a special focus on how governance prepares, supports and monitors the alignment of business needs to the management of the IT domain.

Let’s run quickly through it: everything starts at the top with, in very broad terms, business needs. We’ve already seen how architecture helps in refining these and turn them into an architecture. This architecture now crosses the bridge to the IT domain and it therefore gets embedded in governance. Governance serves three important functions: first of all it evaluates (everything) against the architecture. From that evaluation, it creates instructions, it directs the IT domain, through its management. These directions feed parts of the roadmap, just like the captain instructs his helmsman to sail a certain course - which might not seem a straight one to the destination, yet the captain knows he’s beating to windward.

From there on, the IT domain manages itself, starting with a planning phase, followed by building and running their solutions. You run it, you monitor it! The IT domain is of course also responsible for the wellbeing of its creations.

Rather independently of all good intentions of the IT domain and its management, results are factual and more importantly will also lead to perception. Perception is a nasty beast, because even if results are 100% in line with the intended goals, this doesn’t mean that the perception will be equally positive. Intended goals are no absolute truth and the proof of the pudding is always in the eating. So it is important to not only monitor results, but also how these results are perceived.

It is not the case that the captain of this ship doesn’t trust his helmsman, he has simply taken on the responsibility for more than just a single course, he is responsible for the entire voyage, the ship itself, for all passengers and for its cargo or mission. When entering the port of destination, he will have to come to terms with his clients. So he simply has to make sure that everything goes according to plan. He therefore also monitors the results and the perception, and also the monitoring within the IT domain itself. All these observations are introduced into the evaluation process as feedback, resulting in refinement, improvements, adjustments and new directions towards the IT domain’s management.

I can’t stress this enough: once again we clearly see that architecture and its governance is not interfering with how the IT domain builds or runs things. It prepares, instructs and oversees the intermediate steps towards the final destination, only influencing the IT domain from the outside, adjusting or adding intermediate courses, based on observations from reality.

The Different Faces of Governance

The model of the organisation and its governance is of course very abstract. What does governance look like in reality? Remember when I introduced the four phases of maturity? I visualised them using the analogy of the car platform. In sequential order, an organisation evolves through four phases of maturity, typically identifiable by business silos, standardised technology, an optimised core and configurable components. Throughout these phases, governance is implemented using matching, yet clearly different techniques, methods, institutions…

When an organisation is still mostly organised as business silos, governance relies mostly on business cases as it main means of evaluation and direction. At the IT domain level, project methodology will focus on planning, building, running and monitoring. Near the end, the business case will often be used to evaluate the outcome. The iterative process is mostly implemented through a sequence of rather isolated business cases.

With the advent of standardisation, we see a lot of governance arise: the creation of an IT steering committee, centralised funding and processes focussing on the renewal of the now standardised infrastructure. At this level we also see the first forms of architecture emerge: especially regarding the infrastructure a formal architecture compliance is pursued, architects are introduced in the project teams to ensure this level of compliance, yet they also introduce an architecture-backed exception process, allowing to deviate from the architecture if in doing so more value is to be reached. Finally, typically also a centralised standards team, oversees a standard project life cycle.

The introduction of an optimised core clearly indicates a much more mature presence of architecture. Whereas the architect was mostly one focused role within the teams, we now see much more and clearly defined roles and responsibilities being introduced: process owners take on specific and specialised focus tasks, following architecture’s guiding principles. Business leadership takes on roles in the project teams, clearly embedding senior management involvement. Not only within the project teams, also at the now clearly defined Enterprise Architecture level, senior management will oversee this, reinforcing their bound at this level. Finally, at this level the role of programme manager also typically enters the stage.

When an organisation reached the fourth level of maturity, when it is able to construct itself out of configurable components, it has probably defined its core in a core diagram, surely experiences the benefits of institutionalised post-implementation assessments, with lessons learned and a strong feedback loop. The introduction of e.g. new technology is performed through a formal research and adoption process. At this level a fully established and autonomous Enterprise Architecture team is present, ensuring that business needs are correctly pursued in the long term vision.

TOGAF

Although I firmly believe that each organisation is different, that each organisation deserves and requires a personalised implementation of the above mentioned governance concepts, I also believe that no one should reinvent all wheels themselves all the time. In the current landscape, the Open Group ↗ has earned its place on the architecture stage. IT4IT, TOGAF and Archimate are merely three out of several standards they manage, that have become de facto standards in this industry.

The Open Group Architecture Framework, short TOGAF ↗, has gained much traction due to its realistic approach that allows it to be used at organisations of a broad range of sizes. Although it is big in its entirety, it is also possible to see its merits in a rather simple basic structure that can also usefully guide smaller architectures. I often feel it especially suits this later case, where the structure helps setting up an architecture and governance structure, or rather validating and if needed refining it. It is in that respect that I like to include it here as an existing structure to continue the exporation of how governance can support the organisation, from an architecture point of view.

Scope

TOGAF consists of several large topics…

- Business Drivers & Goals

- Architecture Development Methods (ADM)

- Business Capabilities, dealing with what is required for reaching goals

… and several frameworks

- Architecture Capability Framework, guiding how do architecture in a controlled/organised way

- Architecture Content Framework, on how to document reusable architecture components

- Enterprise Continuum and Reference Models, focussing on feedback loops

From an architecture perspective, especially much value is to be found in the ADM, the Architecture Development Methods.

Architecture Development Methods

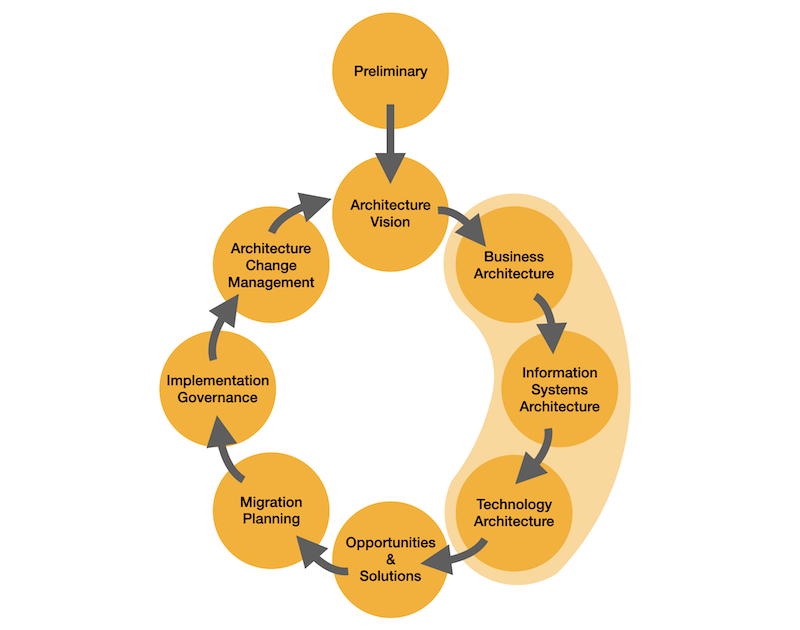

ADM is beyond any doubt the heart of TOGAF. It provides guidance for creating a valuable architecture for an organisation. It follows an architecture development cycle, consisting of 9 phases:

In the preliminary phase, preparation for, customisation of an setting the stage for the architecture is performed. The development cycle is iterative, the preliminary phase is really preliminary and is not part of the iterative aspect. After the preliminary phase, the first iteration starts with the development of the architectural vision.

The architectural vision phase focusses on scoping and creating buy-in with all stakeholders. It’s the Enterprise Architect performing his magic. ADM’s development cycle sees the following three phases as a sequence, I personally see them as executed in parallel and joining back together before the opportunities & solutions phase.

Business Architecture, dealing with changes in workflows, processes and organisational structure, Information Architecture, dealing with data, both in logical and physical form and Technology Architecture, focussing on hardware, software and platforms in general, all take an important subscope from the Architectural Vision and take a deep dive into their respective area of expertise, bringing up the best of breed in each of them. Together with the vision, they basically define thé Enterprise Architecture for the organisation. Only with all this information at hand, the next phase can be undertaken.

Within the Opportunities & Solutions phase a roadmap with iterations of projects is defined, needed to realise the current version of the architecture. This roadmap creates the first actual materialisation of the masterplan, one that can actually be projected against several axes: financial, timing, capabilities…

This is what is basically done in the Migration Planning phase, where an estimation of the actual business value, along with setting priorities on dependencies, costs, benefits and risks.

The Implementation Governance phase verifies if the acceptance criteria, that were set out at first, are actually met.

As a final phase, the Architecture Change Management phase manages risks in function of the realisation of the vision. Here refinements towards the next iteration of phases can be created and applied.

Essentially, this is very little different from the abstract model we presented just above. The same organisation and management best practices return. And that is good. It confirms that several different models can bring the same value to the table. With TOGAF this value is an industry standard, so if you can construct an architectural framework for an organisation and incorporate many of these phases, the result will at least be supported by a trustworthy foundation of inspiration.

TOGAF as a Resource

TOGAF is full of architectural gems. Working your way through its entirety is no small task. Part IV of the standard, the Resource Base ↗, includes several great reference resources that support day to day architectural work. Given that the general concepts and development life cycle is understood, these resources are a great resource of useful architectural knowledge.

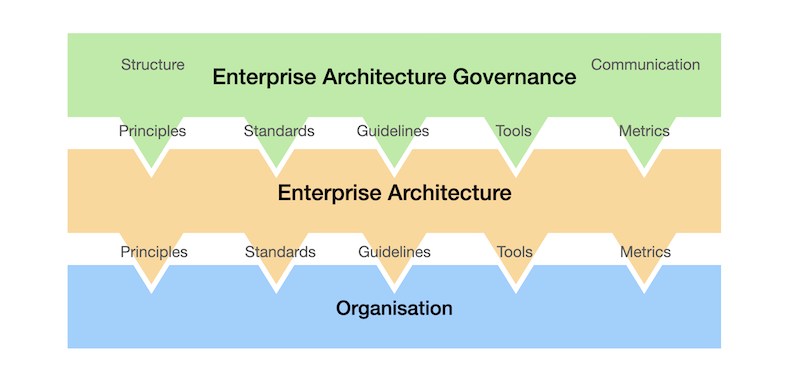

One example is the Architectural Principles ↗. These are essentially guidelines to be respected when elaborating the architecture. These principles are chosen and can be vastly different from organisation to organisation. They are in fact the DNA that specifies how everything out of it is constructed. Having a well though-through set of architectural principles is an enormous aspect of the overall architectural vision.

When defining your set of Architectural Principles, take time to clearly describe them. TOGAF offers a great example on how to do this in a very nice way. Four aspects are of utter importance:

- a name to refer to the principle

- a statement acting as a one-line, an elevator pitch explanation of the principle

- a rationale why the principle is of importance and why in the given context

- every guideline has implications and being very clear about them upfront shows the effort that has been put in selecting the principle and its format

Although every organisation is different, there are principles that can and often should fit any architecture. Here are a few examples that come to mind:

- Maximize Benefit to the Enterprise

- Information Management is Everybody’s Business

- Business Continuity

- Data as an Asset

- Data is Shared

- Data is Accessible

- Ease-of-Use

- Control Technical Diversity

Connecting Principles to Business Strategy

There was of course a reason why I picked architectural principles as an example of knowledge from the TOGAF Resource Base 😇 Architectural Principles are a key success factor to the realisation of an organisation-wide successful architecture.

An important first step in implementing them is by making the connection to the business strategy clear. It’s important to keep on thinking about architecture in terms of alignment of business and IT. Architectural Principles are a great way to thicken this alignment. So how can an architect connect them to the business strategy and make them part of the alignment?

As with any guidelines or rules, the key to make them successful is to make them acceptable, which basically boils down to making them relevant, not just a thick in a box, architecture compliant. The reason why the principle is adopted (which should be at least partially found in the rationale) must be anchored in the actual organisation and in light of the business strategy. If people understand why something is important, they are far more willing to go the extra mile.

Make it something that is part of a bigger whole. By embedding the principles in the project methodology, they become part of the operational realisation of the architecture and thus serve as a forward outpost for the architecture itself.

Finally, after explaining why and embedding it in existing and/or pairing it with other required processes, you can also introduce incentives. Who doesn’t love a reward. In this case the reward comes at the evaluation, the review, the retrospective… If the project was completed successfully, the overall result is considered “ok”. When applying the architectural principles in the project helped in actually also implementing parts of the architecture , the overall result is considered “ok with a +” and if during the project efforts were made that helped to improve the architecture, the project will score a “ok with a double +”. Or something appropriate to the organisation’s usual quotations.

The Cost of Principles

Principles typically are costly. They often add some overhead and that overhead needs some return somehow. If I had a € for every time I’ve heard the phrase “Very nice, but our project isn’t going to bare the cost for that principle.”

When asking projects to adhere to architectural principles, a good approach is to ensure that it is clear that the cost is split among multiple projects, so that all benefit more from a smaller part to bare. In the unlikely event that a principle would only be applicable to a single project, architecture should chip in an pick up the tab. Else, if architecture isn’t willing to do that, it might not be a very important principle after all.

To close this chapter on architecture principles, here are five more:

- connect strategic objectives

- include tradeoffs

- create buy-in from leadership

- enable the use of …

- pragmatism

Go and Spread the Word