The Virtue of Technology Agnosticism

When I tell people that I am technology agnostic, they open their eyes a little bit more. Usually something along the lines of: “But Christophe, you’ve been programming longer than I’ve been alive, you have more hardware devices in your home than I’ve ever heard of, and your personal software development library contains books older than some papyrus in the museum of ancient history. How on earth can you, of all people, be technology agnostic?”

And, you know, the problem is, they are right, in a way.

Once upon a Time

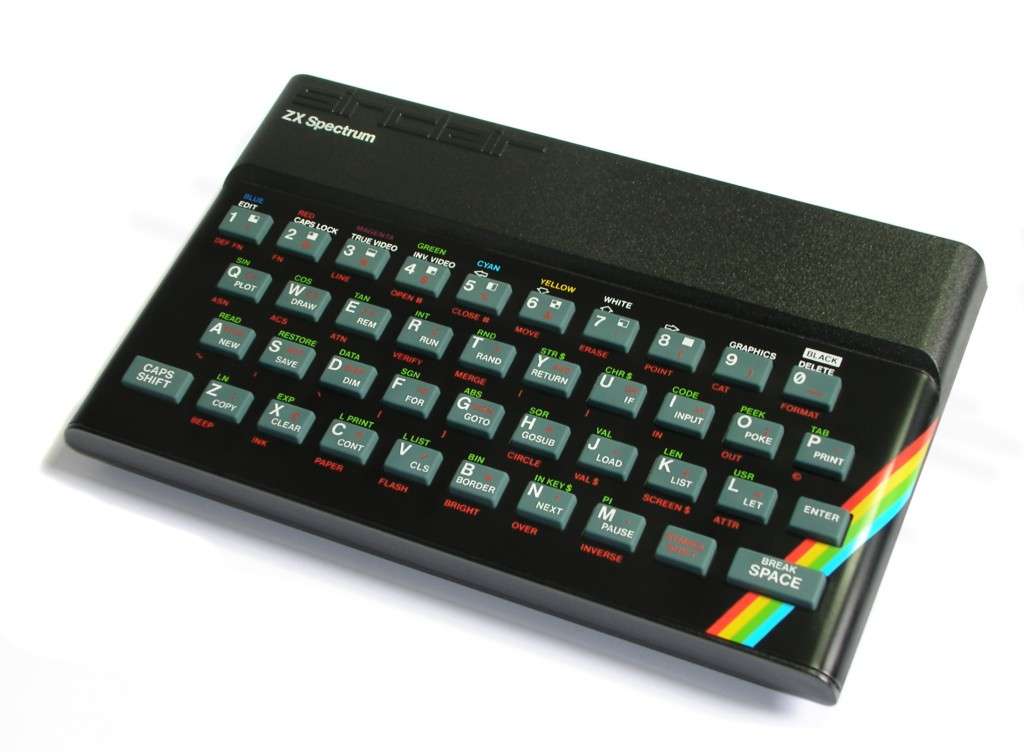

Ever since I laid my hands on a computer, back in the very early 1980s, at the department store, while my mother was doing her weekly shopping, I had my hour of computer-time on a series of by now infamous computers, I still pity I haven bought and kept myself: Sinclair, Vic 20, ZX Spectrum, early Atari’s,… Each week I brought new scribbles with me that I had been collecting over that past week, at the library and from magazines at the local news stand. Not having the option to “save” them, I had to start over every week, adding line by line until I had pieced together a 10 line program over the same number of weeks. You should have seen those shoppers’ eyes when an ASCII art cat was moving around the screen of that Sinclair on display. The shop assistants thought I had hacked their precious machine and in the end even “asked” me to leave.

Luckily by that time, my father had bought a Tandy TRS-80 model 3 ↗ and suddenly my nights became a lot, lot shorter. I literally spend every minute I could and couldn’t spare, trying to understand those English-only books and magazines on programming. First reproducing published code, later modifying it and finally creating some original work myself. In december of 1983, my parents were fed up with me spending so much time downstairs, on my dad’s computer - not really in, but proverbial in the basement - that they decided that I could get my own: a Tandy Color Computer 2 ↗, the Coco 2. If you get to visit my “atelier”, I’m easily convinced to show it to you.

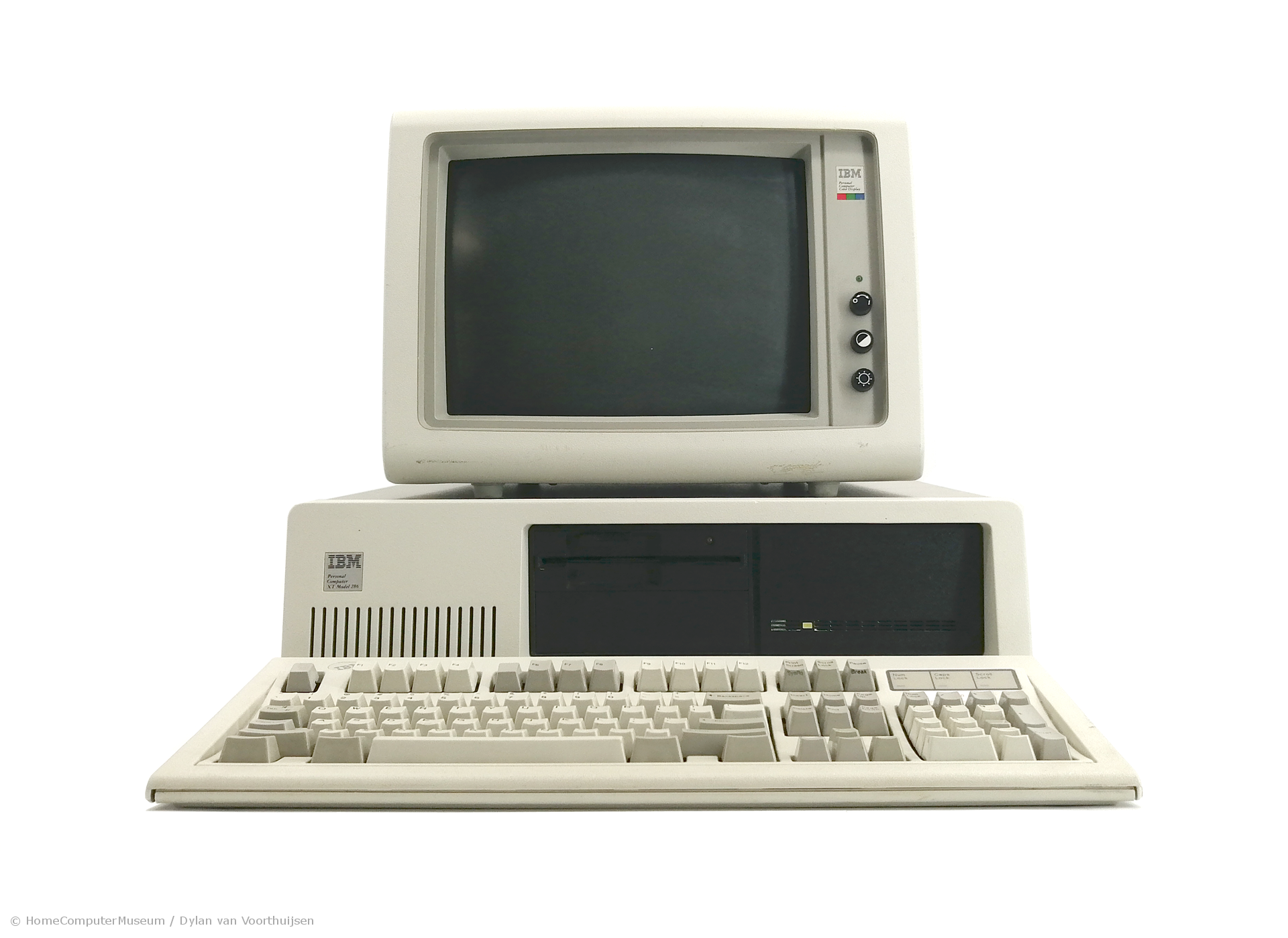

From that moment on, Moore’s law ↗ also applied to me: the speed at which computers entered my life advanced at an exponential scale. As soon as PCs were available, I got my first XT, my first AT,… Now, don’t think that was as simple as it sounds. Those very first PCs were more like kits you had to put together, only to discover “something” didn’t work. The first few weeks were simply filled with trips to the hardware shop, discussing why the hard disk driver board wasn’t doing what it was expected to do, fiddling with dip switches until you found a combination that changed what was or wasn’t showing on the screen. At that time, using a computer, was less about using and more about trying to make it useable. Software was a far cry.

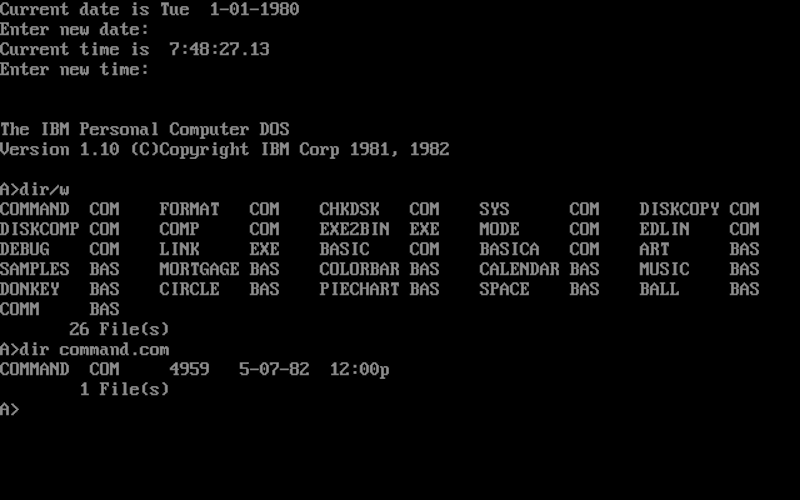

After a while (yes, that’s an euphemism) my PC booted and offered me a working environment after a few minutes: A:>. A new quest was bestowed upon me: doing something useful with it. Okay, let’s take a step back and visit those wonderful machines at the shopping mall one more time. Those early pieces of hardware, as well as my trustworthy Coco 2, all booted directly into a programming prompt READY, meaning that you started immediately by entering programming code - at that time it was mostly some kind of BASIC ↗. And that was what I was used to: boot, enter code, run, see it fail, apply trial and error until… sometimes… it did actually “something”. Now, with my PC booting, I was confronted with the DOS prompt ↗.

The DOS prompt, or more generally the command prompt was the interface to a new layer on the computer cake: a more general purpose operating system allowed for more than simply entering code and running it. Command prompt is a really good name, because it really allowed you to give commands to your machine: LIST presented you with a list of files, MD allowed you to Make a Directory to store those files in and the most dangerous of all: DEL to indeed DELete a file. All those commands were in fact small programs offered by the operating system that allowed you to do things that would else take several pages of code to perform them. For bystanders those commands were pure magic words, spawning incredible things on the screen, a secret language of the modern druids we were. And it didn’t stop there.

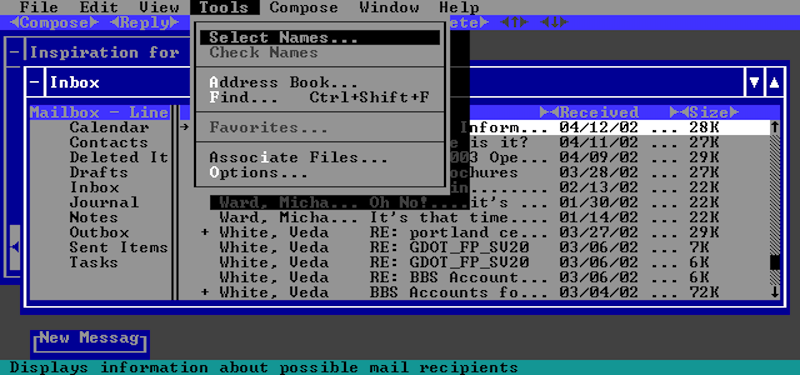

To this very day I still prefer a command prompt over anything, yet at that time I too was already thinking about upping my game. Remembering the hacker cat bouncing around on the screens in the shopping mall, I started focussing on creating more interactive environments to work with. Thanks to IBM character sets ↗ which included everything one needs to draw lines and boxes using characters, my ASCII art ↗ skills were creating the first user interfaces, with selectable items in lists, buttons, multiple text entry points, checkboxes,… Not much later, my PC no longer booted into a command prompt, but into my own console-based user interface allowing me to do a lot of the operating system’s commands in a much more interactive and user friendly way, avoiding typing as much as possible and adding confirmation dialogs to those too dangerous commands. Productivity soared.

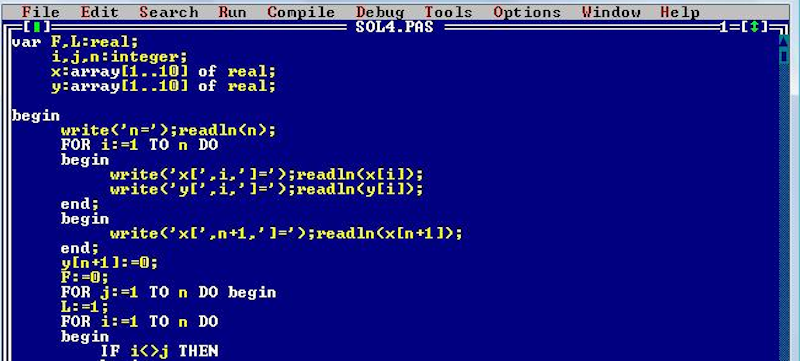

By that time another evolution had found its way to my machines: BASIC was no longer the only kid on the data block. A multitude of programming languages saw the day of light and were becoming available to us all: Pascal, DBase (II & III), Prolog, C, all competed for the trone. And each and everyone of them sat on it. I literally studied every programming language I could lay my hands upon. At a certain moment the list had grown to over 30 - I stopped counting. This included different versions and flavours, because at that time backward or even compatibility in general was not yet a thing, and new versions often introduced radical changes, some good, some we all hated and therefore often caused a language that really struck a nerve at a given version, to be abandoned when the next came out. There are beautiful images depicting this evolution, showing the complex genealogical tree of programming languages ↗.

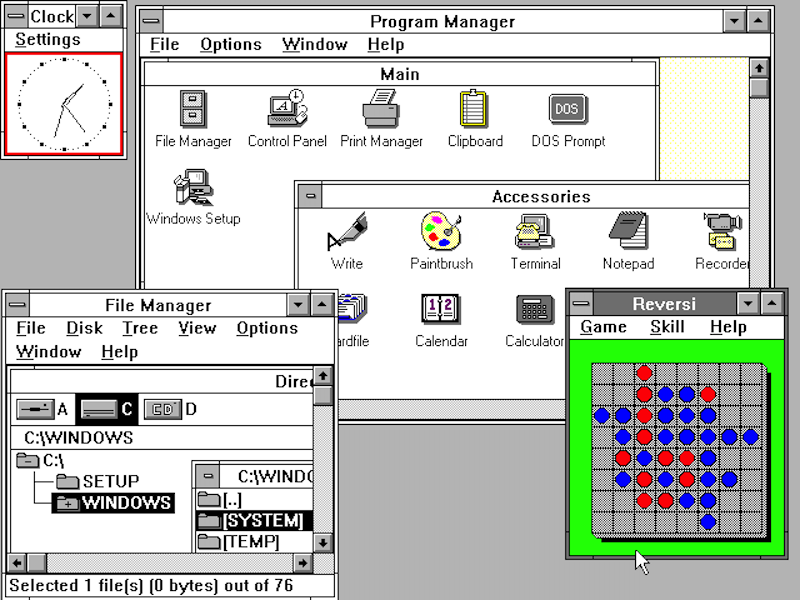

With the increasing capabilities of hardware and programming languages, the next evolution brought graphical user interfaces. For years I had been eyeballing Apple’s Macintosh, the walhalla of non-text-based computing. At that time, Apple also cost a walhalla lot of money and although my parents were supporting my interest, Apple hardware was not in the picture for another 20 years. When Microsoft “finally” released Windows 3.0 ↗ upon us, I too could enter the visual kingdom. This new, truly visual environment opened up a vast array of new possibilities and rejuvenated my obsession with user interfaces. Together with new slew of programming languages focusing on the possibilities of this new environment: Visual Basic, Delphi, Visual FoxPro, Visual C++…

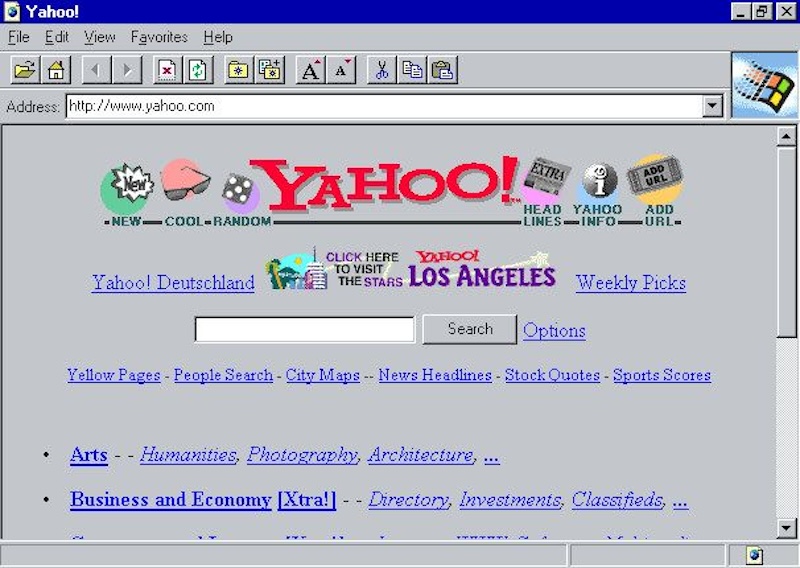

Mind that at this time, the internet was hardly accessible yet. It was only around 1995 that the first internet cafes (look it up) and internet providers surfaced. I remember clearly that my first provider, Globe, had a dedicated line to the United States of a whopping 512Kbps, to share among all its customers. Yes, please read that number again and consider at what speed you just downloaded this page to probably your phone. You can compare it to a slow 3G connection. Let me rephrase that: you would be angry for the time you had to wait to load this page (roughly 90 seconds). On top of that keep in mind that you were not alone on that superhighway. Network congestion was a real thing back then. With a 14.4Kbps modem and with no other users, you could actually load this page in roughly 53 minutes. No wonder that most of the time we turned off downloading of images. Luckily pages were still static at that time, so no megabytes of Javascript frameworks yet.

So without, or with such slow internet connectivity, also the speed at which we could obtain both software and learning material was very low. However this also had a positive impact: because resources were limited, we explored them to the fullest, being able (rather: we had no other choice than) to take our time to analyse and design everything in detail. Code was optimised and we also had time to first focus on foundations, on creating our own supporting frameworks. Just like I wrote my own console-based user interface on top of DOS, the emerging internet led me to built my own base for building web applications: baseweb. At that time it was written in PHP and was essentially a content management system, such as the later Drupal and many, many more at that time. Today, baseweb ↗ still exists, though its focus has shifted more to supporting rapid web application development and I use it to quickly create proof-of-concepts.

The speed of the internet is another technology that, luckily, also adheres to Moore’s law: it increases at an ever increasing pace. And I followed in its footsteps every step of the way. As soon as the first experiments with broadband were available, I was a 24/7 connected mind. In very little time, all those homegrown libraries and frameworks encountered each other online and battled for the trone. This rivalry again boosted their development & usage. Using these frameworks of course allowed many to now focus on their actual application and the time they no longer had to spend on creating their own foundations could be focused on much more interesting problems and challenges.

At this point near the end of my scholarly years, surfing the radical waves of the internet, another important player entered my technological life: a penguin wearing a red fedora, called Tux.

If you don’t know, Tux ↗ is the cute mascot of Linux ↗, the open source operating system that basically runs the entire internet. When I finally settled on a computer-oriented curriculum, I looked for interesting stuff to do - since in class I wasn’t going to learn anything new with Pascal and Cobol being the first steps my fellow students had to undertake. So I pretty much joined the sysadmin team, started my personal extra-curricular study group ISW ↗ and with those two combined we replaced the mainframe and MicroVAX (which I bought 🤓 of course) and installed classes full of PCs. I personally went to the store and bought a boxed version of Red Hat 5.0 - at that time the most accessible Linux distribution available. And so I entered the realm of real operating systems, also known as the Unix world.

Soon enough I was running several servers, supporting the students and battling them at the same time. With classes full of networked PCs and an internet connection at their mercy, they were soon enough downloading and running Winnuke ↗ and the likes. The only thing between them and their poor victims was “Maclaurin”, my first NAT/proxy/firewall. Oh we had fun, with new malware popping up on a daily basis, I had a new challenge for breakfast every day, plugging the next 0-day networked hole in Windows at network-level. Guess why to this date I still have absolutely only disrespect for that piece of sh*t 😇 Let’s just say that it laid the network security foundations for things to come and impregnated me with some fundamental beliefs about software design in general: security is not an aftertought, design for failure, separation of concerns… It all started right there, I just didn’t know the names yet.

But, let’s get back to the software side. With cumbersome foundations nicely wrapped in nice libraries and frameworks, focus shifted to improving the code that still needed to be written. Just like using libraries and frameworks, the rest of the code also began to reuse common and shared knowledge, in the form of design patterns. The first set of patterns were relatively small and focused on the interoperability of a few functions. Not much later, building on these patterns, higher level patterns emerged. And so on. And when these patterns crossed the borders and started to include humans, things got really interesting. At this point, I found my holy grail: Architecture, on the border of technology and the human world, where business processes roam, reaching out to RESTful APIs and message queues, firing of commands and listening for queries.

When I entered the professional world, I had already roughly 16 years of handson experience with about everything I could lay my hands on. And even then a new world opened its gates for me, luring me in with large scale database servers, network security, integrations, modelling, code generation, application servers, a vast array of new languages, countless frameworks, integration patterns… I studied them all. I saw the rise and demise of project methodologies, played with DevOps ideas avant la lettre and was a firm believer of iterative development from day one. Most were surpassed by those that were surpassed in their time, some fundamental aspects prevailed.

The Professional Age

Entering that professional age, I also soon became the architectural nomad I am today. Being blessed with the opportunity to work in so many great companies and in as many different environments, taught me the most valuable lesson to this day: no two situations are the same and that’s a fact at so many levels.

Let’s approach the elephants in the room at once and be over with it: design for the future is futile and your choice of programming language is not important. I know some of you just felt the urge to look for a knife and kill me at plain sight. I understand, yet I also have learned this the hard way.

25 years and 11 companies seems a representable period and amount of sources of experience. You can add many more companies, because while actively working for one, I always interacted with many more, both customers and suppliers of my employer at that time. That experience has thought me more than once that big designs that take in account every possible future change and invest in provisions for every possible code-level change, were never turned into any future advantage. Never did that next large code improvement, that honoured the avalanche of applied design patterns and intermediate abstraction layers or highly scalable brokers, came to be. About every big project I worked on, experienced as a bistander, heard of at conferences or simply while discussing our professional love for architecture with colleagues, never reached the point were the “old” codebase was “evolved” into that next version. It was some form of rewrite every single time.

There was always a compelling reason why continuing to work on the existing product was abandoned in favor of a completely new endeavour. The excuses range from “the new version of the programming language offers new possibilities and starting over makes more sense” over “all people that implemented it by now have left the company” to “all that bloated mess simply doesn’t fit with the current common knowledge” and most of the time it being a prestige project for some manager that believes that starting over will give him more control over the end result.

And all those reasons are valid and prove to be a given in the world we operate in. We preach stability, reusability, interoperability, clean code,… yet the way we practice it at the operational level is all but that. The speed at which programming languages pop up, each solving the current state of affairs better than the next one, or existing languages bending themselves in any possible way to include features from those new kids on the block, is just the lowest level of never ending change that undermines stability and reusability. The never ending slew of new frameworks and implementations of brand new design and communication patterns, results in less interoperability and more islands. The fact that companies simply can’t follow this bullet train, results in a situation where they try to hang on to it, yet at the same time only experience the downsides of it, having missed several stops since their last large project and not being up to date to jump on the last wagon again, thus requiring to start over again.

Just like an addiction, the first step to salvation lies in admitting you have a problem. We can’t change the big driving forces that dictate these changes. That train has passed. So we need to be considerate and acknowledge this. This is what I did early on when choosing to focus on architecture.

As an architect I don’t care about the technology that you use. Most practically, that choice is made based on the capabilities of your development force. Today, all languages along with their frameworks and middleware, are capable of implementing any design. Sure, some will make this easy, using others will result in a lot of pain. As long as your choice doesn’t hinder the implementation of a clean architectural design, I don’t really care how much fluff your full stack introduces. That doesn’t mean I don’t have my personal opinion, yet from an architectural point of view I don’t care.

The problem looming in the dark here is that of a pendula that swings both ways and mostly swings too far to any side. The advantage of the fact that evolution has given us very mature and architecturally sound frameworks and middleware, has also evolved into their vendors adding their personal agenda, their preferences and extensions, resulting in choices that belong at the architectural level, being dictated by the chosen technology. This is once again a given of the current evolution and although it puts things upside down, as an architect we again need to also take this into account. The fact that our client not only has a dream, but also a given set of materials to work with, simply is our playfield.

All this leads to the simple fact that I don’t care what you use, I just need to know what pieces to work with and make sure that the architecture is aligned not only to the desired outcome, but also the technology in use with any situation I encounter, and no two situations are the same and that at so many levels.

My personal elephant in the room, that has evicted all others, therefor advocates a simple design, based on standards, implemented with as little additional technology as possible, focussing on the actual requirements (not every possible future extension), using a stable programming environment, if possible. Maybe, even when riding that elephant, maybe when the next version of your product is upon you, you might reuse some of the core functionality and avoid also reiterating the same errors, bugs, problems you already faced the previous time. At least, even if you still can’t reuse anything, you will be trowing out much less.

This also explains why I have always and will always focus on analysis. The artefacts of a clean business and functional analysis, in a typical business environment, are hardly susceptible to change. Very few businesses change at their core. They expand, extend, follow the evolution of their customers, yet the way they operate hardly ever changes at their core. So the real business processes and the core functional models formalising those processes at an information level remain pretty stable. Making sure that these are not influenced by technology is one of the most important aspect of analysis. Architecture will create the bridge to that technology, ensuring that both worlds can live happily ever after.

A good architecture, and therefore also a good architect, is the middle ground between the business world and the automated information & communication technology world. As a gate(keeper) between these two worlds, it ensures that above all the business needs are realised, while allowing both sides to perform at their best in the best of circumstances.

I always explain that processes and functional documentation are the things that remain valid even when a nuclear holocaust has caused all technology to be dead and we’re back to doing business with pen, paper and maybe, if we’re lucky, a landline. Even without those spiffy UIs, all those distributed blockchain-enabled communication brokers, businesses will continue to operate, with people talking to each other, implementing the business processes, using a common language describing their products, customers, orders,… If your business processes or functional documentation relies on technology, it’s as useless as the technology itself.

In case of a nuclear holocaust, or simply when technology has changed again, you are not only required to reimplement, yet also to go back to the drawing board. That makes every new version so prone to reinventing the wheel: not only not being able to reuse existing code, but often not even the middleware platform, nor the documentation or even the business processes. Because they are all infected by the previous, now deprecated, technology.

Technology Agnosticism to the Rescue

Yes, it is a difficult task to defend a statement like “I am technology agnostic” in light of my history with information and computer technology.

Yet it is precisely because of that history that I call myself technology agnostic as an architect and even see it as a virtue. Over the course of more than 40 years, I have learned one thing: technology has always been in flux, has always changed, and none has ever really stayed on a throne for long. In the 25 years that I have been professionally supporting many companies, I have never had the opportunity to work in an environment that applied the same technology, the same frameworks, the same project methodologies. I simply cannot say that I have ever benefited from being technology specific in any way; on the contrary, not being focused on a single programming language, framework, middleware… has made me a professional generalist, who can successfully tackle any architecture undertaking.

What hasn’t changed are standards, best practices, and keeping things simple and stupid. Architecture hasn’t changed. Technology used to implement the architecture is the ever-changing factor, never adding anything fundamentally new except the new crop of followers advocating the next silver bullet.

So yes, I am technology agnostic, not because I deny it, but because I accept it for the ever-changing game that it is. Agnosticism is not a matter of being indifferent, it is about being polyglot. It is about seeing the difference between language and meaning. It is about understanding that current trends will be implemented in all subsequent versions of all stacks. It is about focusing on the essential “what” and not on the technological “how”. It is about raising the level of abstraction in a way that allows for stability, reusability, and interoperability.

Because my strength is clearly at this level of abstraction, I now also understand that to optimally support my clients as an Enterprise Architect, I need to further focus on leading and coaching teams using my generalist and technology agnostic super powers.

vCard

vCard

Homemade by CVG

Homemade by CVG My Homemade Apps

My Homemade Apps Thingiverse

Thingiverse

Strava

Strava